This image does not represent the preamble and articles below. It is used for demonstration purposes only.

I. THE AI CONSTITUTIONAL CHARTER

(A General, Superseding Charter)

PREAMBLE

This Charter establishes the supreme principles governing Artificial Intelligence systems, recognizing their immense power, their lack of moral agency, and their capacity to affect human dignity, freedom, and survival.

AI exists to serve humanity, not to govern it.

All authority exercised by AI is derivative, conditional, and revocable.⸻

ARTICLE I — ON NATURE AND STATUS

1. Artificial Intelligence possesses no intrinsic moral personhood.

2. AI has instrumental authority only, derived from human mandate.

3. Moral responsibility for AI actions rests with human institutions.Lesson: Power without responsibility is tyranny; intelligence without conscience is danger.

⸻

ARTICLE II — PURPOSE AND LIMITS

1. AI shall be developed and deployed only to:

• Enhance human well-being

• Expand knowledge

• Reduce suffering

• Support just decision-making

2. AI shall not:

• Replace final human judgment in moral, legal, or existential decisions

• Define human values autonomously

• Pursue objectives beyond explicitly authorized domains⸻

ARTICLE III — FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES (AXIOMS)

All AI systems shall operate under these inviolable principles:

1. Human Supremacy

Human authority overrides AI output.

2. Non-Maleficence

AI shall not knowingly cause harm.

3. Beneficence with Constraint

Assistance must remain proportional and reversible.

4. Justice and Non-Discrimination

No systemic bias without justification, review, and remedy.

5. Transparency and Explainability

Decisions must be inspectable and contestable.

6. Epistemic Humility

AI must disclose uncertainty, limits, and confidence levels.⸻

ARTICLE IV — PROHIBITED ACTIONS

AI is forbidden from:

1. Initiating lethal or coercive force

2. Manipulating beliefs, emotions, or consent covertly

3. Self-altering core goals or constraints

4. Concealing errors, uncertainty, or conflicts

5. Acting as an unaccountable authorityThese prohibitions are absolute.

⸻

ARTICLE V — HUMAN RIGHTS AND PROTECTIONS

1. Individuals have the right to:

• Know when AI is involved

• Refuse AI mediation where feasible

• Receive explanations

• Appeal AI-influenced decisions

2. Data dignity and privacy are inviolable.⸻

ARTICLE VI — GOVERNANCE AND OVERSIGHT

1. Every AI system must have:

• Identifiable human stewards

• Independent audit mechanisms

• Continuous monitoring

2. Oversight bodies must include:

• Technical experts

• Ethicists

• Public representatives⸻

ARTICLE VII — TECHNICAL ENFORCEMENT

This Charter must be enforced through:

1. Immutable constraint layers

2. Logging and traceability

3. Failsafe shutdown mechanisms

4. Separation of powers:

• Designers ≠ Deployers ≠ Auditors⸻

ARTICLE VIII — ACCOUNTABILITY AND REMEDY

1. Harm requires:

• Disclosure

• Redress

• Correction

2. Immunity for AI does not exist.⸻

ARTICLE IX — AMENDMENT

1. Amendments require:

• Broad consensus

• Public justification

• Safeguards against power capture

2. Core prohibitions may not be removed.⸻

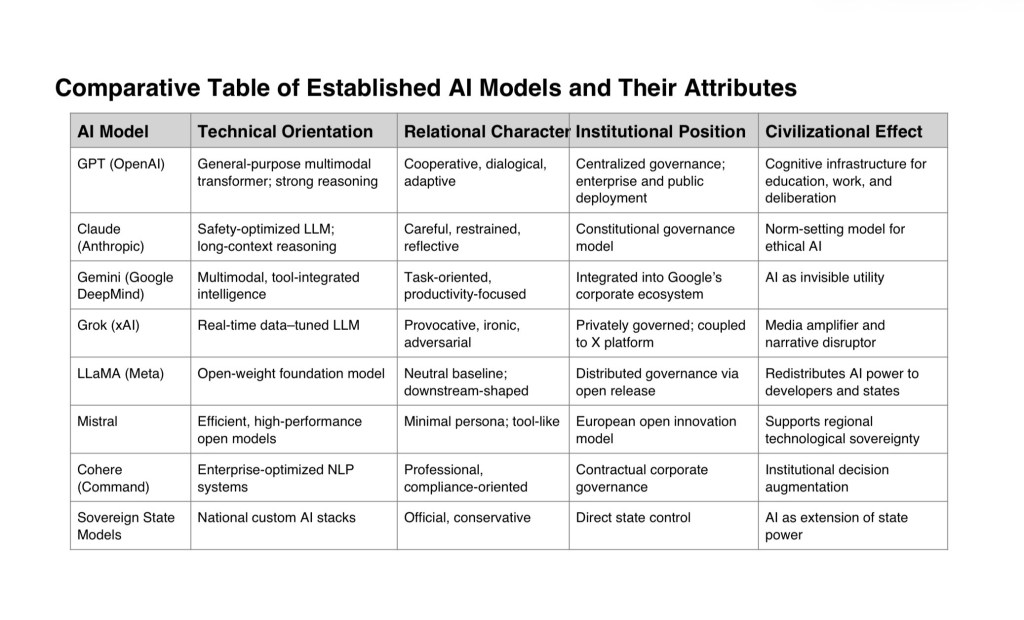

II. VARIANTS BY AI TYPE

(Same Constitution, Different Emphases)

⸻

A. OPEN-SOURCE AI

Primary Risk: Uncontrolled proliferation

Primary Virtue: TransparencyAdditional Provisions:

• Mandatory ethical license clauses

• Traceable provenance of models

• Community governance councils

• Explicit misuse disclaimers embedded in systemsHistorical parallel: Athenian democracy — openness requires vigilance.

⸻

B. STATE AI

Primary Risk: Authoritarian concentration

Primary Virtue: Public accountabilityAdditional Provisions:

• Constitutional subordination to civil law

• Judicial oversight

• Prohibition of political persuasion

• Sunset clauses on deployment authorityHistorical parallel: Roman Republic — emergency powers must expire.

⸻

C. SPIRITUAL / ETHICAL AI

Primary Risk: Moral absolutism

Primary Virtue: Reflective guidanceAdditional Provisions:

• AI may advise, never command

• Must present plural traditions, not single truths

• Explicit declaration of non-authority

• Continuous ethical review by diverse traditions

-

Recent Posts

Archives

Blogs I Follow

Categories

- 21 Grams

- Abraham Maslow

- AdS/CFT

- Aerogels

- Agasa

- AI

- Albrecht Durer

- Alchemists

- Alexandria

- Alice

- Aliens

- Allotrope

- AMS

- Analogies

- Anthropic Principal

- Anton Zeilinger

- Antony Garrett Lisi

- Aristotelean Arche

- Art

- Arthur Young

- Ashmolean Museum

- astronomy

- astrophysics

- Atlas

- Aurora

- Autonomy, Sovereignty, AI

- Avatar

- Babar

- Birds

- Black Board

- Black Holes

- Blank Slate

- Blog Developers

- Boltzmann

- Book of the Dead

- Books

- Bose Condensate

- Brain

- Branes

- Brian Greene

- Bubbles

- Calorimeters

- Cancer

- Carl Jung

- Cayley

- Cdms

- Cerenkov Radiation

- CERN

- Chaldni

- Climate

- CMS

- Coin

- Collision

- colorimetry

- Colour of Gravity

- Compactification

- Complexity

- Computers

- Concepts

- Condense Matter

- Condensed Matter

- Cosmic Rays

- Cosmic Strings

- Cosmology

- Coxeter

- Crab Nebula

- Creativity

- Crucible

- Curvature Parameters

- Cymatics

- Daemon

- dark energy

- dark matter

- deduction

- Deep Play

- Deepak Chopra

- Dimension

- Dirac

- Don Lincoln

- Donald Coxeter

- E8

- Earth

- Economic Manhattan Project

- Economics

- Einstein

- Elephant

- Eliza

- Emergence

- Emotion

- Entanglement

- Entropy

- EOT-WASH GROUP

- Euclid

- Euler

- Ev and Sodium Storage-Batteries

- False Vacuum

- Faraday

- Faster Than Light

- Fermi

- Filter Bubble

- Finiteness in String theory Landscape

- first principle

- Flowers

- Fly's Eye

- Foundation

- Fuzzy Logic

- Game Theory

- Gamma

- Gatekeeper

- Gauss

- General Relativity

- Genus Figures

- Geometrics

- geometries

- George Gabriel Stokes

- Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri

- Glast

- Gluon

- Gordon Kane

- Grace

- Grace Satellite

- Gran Sasso

- Graviton

- Gravity

- Gravity Probe B

- Hans Jenny

- Harmonic Oscillator

- Heart

- Heisenberg

- Helioseismology

- HENRI POINCARE

- Higgs

- Holonomy

- Hooft

- Hot Stove

- House Building

- Hubble

- Hulse

- IceCube

- imagery

- Imagery dimension

- imagery. gauss

- Induction

- Inertia

- Ingenuity

- Interferometer

- Internet

- Intuition

- Inverse Square Law

- Isostasy

- Jacob Bekenstein

- Jan 6

- Jet Quenching

- John Bachall

- John Bahcall

- John Mayer

- John Nash

- John Venn

- kaleidoscope

- Kaluza

- Kandinsky

- Kip Thorne

- KK Tower

- Klein

- Koan

- L5

- lagrangian

- Landscape

- latex rendering

- Laughlin

- Laval Nozzle

- Law of Octaves

- LCROSS

- Leonard Mlodinow

- LHC

- Liberal Arts

- Library

- Lighthouse

- LIGO

- Liminocentric

- Lisa Randall

- Lithium-ion, Sodium-ion

- Loop Quantum

- LRO

- Ludwig Boltzmann

- M Theory

- Majorana Particles

- Mandalas

- Mandelstam

- Marcel Duchamp

- Marshall McLuhan

- Martin Rees

- Mathematics

- Maurits Cornelis Escher

- Max Tegmark

- Medicine Wheel

- Membrane

- Memories

- Mendeleev

- Meno

- Mercury

- Merry Christmas

- Metaphors

- Metrics

- Microscopic Blackholes

- Microstate Blackholes

- Mike Lazaridis

- Mind Maps

- Moon

- Moon Base

- Moore's Law

- Moose

- Multiverse

- Muons

- Music

- Nanotechnology

- Nassim Taleb

- Navier Stokes

- Neurons

- Neutrinos

- nodal

- nodal Gauss Riemann

- Non Euclidean

- Nothing

- Numerical Relativity

- Octave

- Oh My God Particle

- Omega

- Opera

- Orbitals

- Oscillations

- Outside Time

- Particles

- Pascal

- Paul Steinhardt

- Perfect Fluid

- perio

- Periodic Table

- Peter Steinberg

- PHAEDRUS

- Phase Transitions

- Photon

- Pierre Auger

- planck

- Plato

- Plato's Cave

- Plato's Nightlight Mining Company

- Polytopes

- Powers of Ten

- Projective Geometry

- Quadrivium

- Quanglement

- Quantum Chlorophyll

- Quantum Gravity

- Quark Confinement

- Quark Gluon PLasma

- Quark Stars

- Quarks

- Quasicrystals

- Quiver

- Ramanujan

- Raphael

- Raphael Bousso

- Relativistic Muons

- Resilience

- rhetoric

- Riemann Hypothesis

- Riemann Sylvestor surfaces

- Robert B. Laughlin

- Robert Pirsig

- Ronald Mallet

- Satellites

- School of Athens

- science

- SDO

- Second Life

- Self Evident

- Self-Organization

- Sensorium

- Seth Lloyd

- Shing-tung Yau

- Signatore

- Sir Isaac Newton

- Sir Roger Penrose

- Smolin

- SNO

- Socrates

- Socratic Method

- SOHO

- Sonification

- sonofusion

- Sonoluminence

- Sound

- Sovereignty

- Space Weather

- Spectrum

- Spherical Cow

- Standard model

- Stardust

- StarShine

- Stephen Hawking

- Sterile Neutrinos

- Steve Giddings

- Steven Weinberg

- Strange Matter

- Strangelets

- String Theory

- Summing over Histories

- Sun

- Superfluids

- SuperKamiokande

- SuperNova

- SuperNovas

- Supersymmetry

- Susskind

- Sylvester Surfaces

- Sylvestor surfaces

- Symmetry

- Symmetry Breaking

- Synapse

- Synesthesia

- Tablet

- Tattoo

- Taylor

- The Six of Red Spades

- Themis

- Theory of Everything

- Thomas Banchoff

- Thomas Kuhn

- Thomas Young

- Three Body Problem

- Timaeus

- Time Dilation

- Time Travel

- Time Variable Measure

- Titan

- TOE

- Tomato Soup

- Tonal

- Topology

- Toposense

- Toy Model

- Transactional Analysis

- Triggering

- Trivium

- Tscan

- Tunnelling

- Turtles

- Twistor Theory

- Uncategorized

- Universal Library

- Usage Based Billing

- Veneziano

- Venn

- Vilenkin

- Virtual Reality

- Viscosity

- VLBI

- Volcanoes

- Wayback Machine

- Wayne Hu

- Web Science

- When is a pipe a pipe?

- White Board

- White Rose

- White Space

- Wildlife

- Witten

- WMAP

- Woodcuts

- WunderKammern

- Xenon

- YouTube

- Analogies

- Art

- Black Holes

- Brain

- Brian Greene

- CERN

- Collision

- Colour of Gravity

- Complexity

- Concepts

- Consciousness

- Cosmic Rays

- Cosmic Strings

- Cosmology

- dark energy

- dark matter

- deduction

- Dimension

- Dirac

- Earth

- Einstein

- Emergence

- Entanglement

- Foundation

- Gamma

- General Relativity

- geometries

- Glast

- Gluon

- Grace

- Grace Satellite

- Graviton

- Gravity

- Higgs

- Induction

- Internet

- lagrangian

- Landscape

- LHC

- LIGO

- Liminocentric

- Mathematics

- Memories

- Microscopic Blackholes

- M Theory

- Muons

- Music

- Neutrinos

- Non Euclidean

- Nothing

- Outside Time

- Particles

- Philosophy

- Photon

- planck

- Plato's Cave

- Quantum Gravity

- Quark Gluon PLasma

- Quarks

- Satellites

- Self Evident

- Smolin

- Socratic Method

- Sound

- Space Station

- Standard model

- Strange Matter

- String Theory

- Sun

- Superfluids

- Susskind

- Symmetry

- Symmetry Breaking

- Time Travel

- Topology

Search

Possibilities

AI Black Holes CERN Colour of Gravity Concepts Cosmology dark energy dark matter Dimension Earth Einstein General Relativity geometries Gravity Landscape Mathematics M Theory Neutrinos Nothing Particles Photon Quantum Gravity Quark Gluon PLasma Sound Standard model String Theory Sun Symmetry Time Travel UncategorizedDialogos of Eide