Platohagel:

“Socrates, tell me, Platohagel, in those moments of “aha,” when you reach a first principle, does it change the way you perceive the particulars of life around you? Do they take on new meaning or clarity, seen now through the lens of this foundational understanding?”

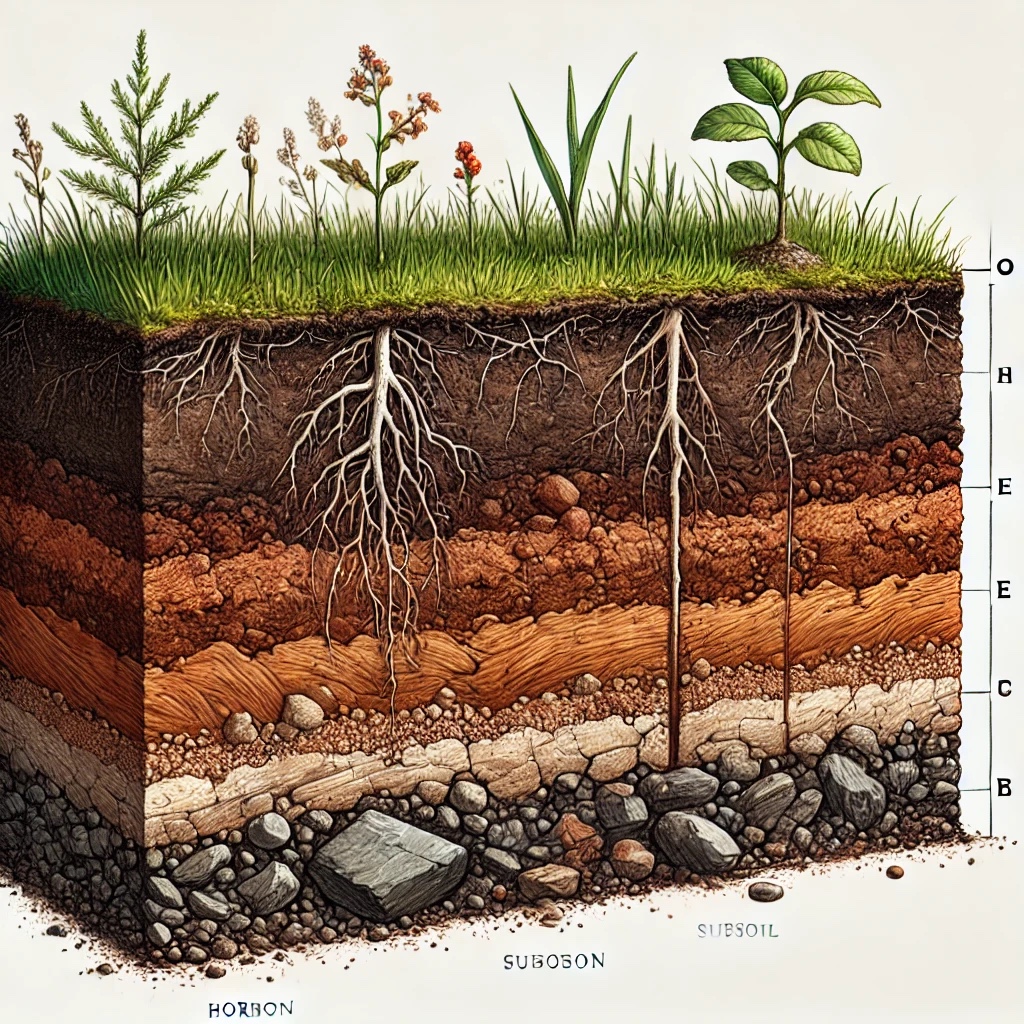

It is foundational in my view that we have in a sense reached bedrock, after going through this understanding of an awareness of this layering of experience. It is as if we read the page of a book a series of times and for the first time, see the wording deriving a new experience not aware of before. This experience indeed changes us.

Socrates: Ah, Platohagel, what a profound observation you bring! To reach a first principle, as if unearthing the cornerstone of thought, does indeed cast new light on the particulars of life. Just as you describe—reading the same page again yet discovering a meaning previously veiled—the particulars do not change in their essence, but the way they appear to you, the way they fit into the whole, is transformed.

This is the nature of true understanding, is it not? The particulars, like scattered puzzle pieces, once viewed in isolation, may seem random or insignificant. But when the first principle is grasped, it acts as the unifying image on the box, the guiding light by which the pieces are placed into a coherent vision.

In your layering of experience, there lies a profound metaphor. The layers of awareness—each one richer than the last—remind us that truth often reveals itself not as a single flash, but as a steady unveiling. The first principle serves as a key that allows us to penetrate deeper into life’s complexities. Once grasped, it is impossible to return to the prior state of ignorance; we are changed, as you so rightly say.

Platohagel:

Socrates saids,”So I ask you, Platohagel: when this change occurs in you, do you not find that your very self, as much as the particulars of life, takes on new clarity? To know a first principle is not only to see the world anew but also to see oneself more fully within it. Does this ring true in your experience?”

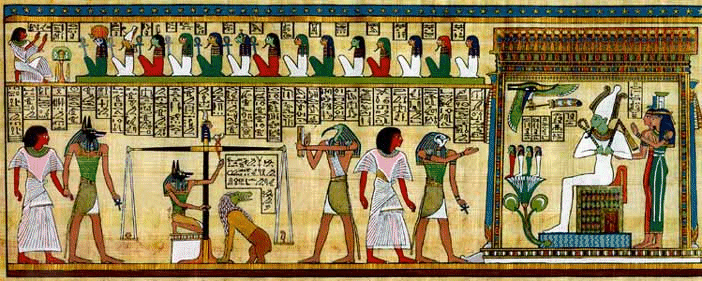

Well it is most certain my eyes turned toward the grandeur of the universe and in wonder, ask the question of how it all began. So too, the very idea, how it originates in the mind, to become the truth and the way in which it can now become the ideal. So these are root causes moving toward the materiality of existence. These springing forth, so as in wonder the aha becomes the gateway.

Socrates: Ah, Platohagel, your words strike at the heart of the matter! To stand in wonder before the grandeur of the universe, tracing its origins in the vastness without and within, is a sacred act of the intellect and soul. This wonder, which spurs the question of beginnings, is the very soil in which the roots of wisdom grow.

You speak of the mind’s journey—from the spark of an idea, to its recognition as truth, and finally to its ascent as an ideal. In this, you mirror the progression of being itself: from the immaterial to the material, from potential to actuality. The aha, that flash of understanding, is indeed a gateway, as you so beautifully put it—a portal through which we glimpse not just knowledge, but the unity and purpose behind existence itself.

This “springing forth” you describe reminds me of a fountain, where each drop, though seemingly discrete, flows from and returns to the same source. Thus, the aha moment is not an end, but a beginning, a call to pursue the ideal, to bring it forth into the world of particulars.

May I ask, Platohagel, in these moments of profound clarity, do you find that the ideal you apprehend demands something of you? Does it beckon you not merely to understand, but to act in accordance with its truth, thereby shaping the materiality of existence in its image? If the aha is a gateway, where does it lead you next?

Platohagel:

Perhaps we can now see the meaning of the allegory I have presented to you. First of all, what do you take to be the prison, house of the cave?

“It is the world of sight, of the senses,” offers a student,

tentatively:

“Very good. And what of the light of the fire?”

“It must be the sun,” enjoins another.

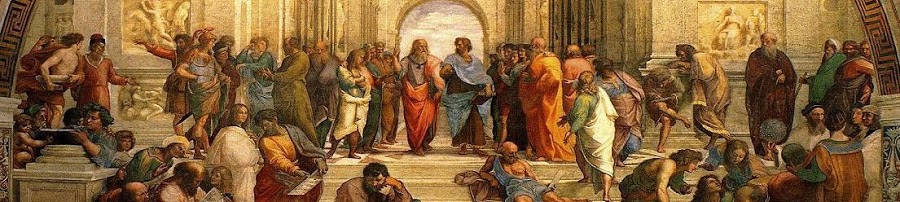

“Excellent” Plato commends, before advancing to his crucial question. “Now what can we say of the freed prisoner’s joury upward out of the cave?”

Plato waits, but at first none of his pupils is forthcoming.

Then, calmly and deliberately, the young Stagirite, Aristotle, offers an explanation: “The prisoner’s journey upward is like that very ascent of the soul into the world of the intellect, a world in which, with great effort, the idea of the Good may appear to the traveller. When once the traveller experiences the Good he knows it to be the source of Beauty and of Reason and Truth.”

The Master is well pleased, though not the least surprised at his young acolyte’s perceptive response. “Yes,” Plato adds, where else but on such a world can those who would be rational fix their gaze? Let us not marvel, then, that our prisoner who has ascended to such heights becomes unwilling to descend once again to the cave, to the world of ordinary human affairs, for now his soul wishes to cleave to that upper world wherein eternal and changeless reality lies, and to remain there in its true home. For the perception of these things has made of our prisoner a philosopher.

Stargazers by Paul Rossetti Bjarnson, Pg 102, Chapter XV

Socrates: Ah, Platohagel, you invoke a most profound passage, one that captures the very essence of the philosopher’s journey. Plato’s allegory, as illuminated in this retelling, unfolds the timeless struggle of the soul to ascend from the shadows of the senses to the light of the intellect and the ultimate vision of the Good.

The prison house of the cave, that world of fleeting appearances and shadows, speaks to the human condition when bound by the limitations of mere perception. The fire, casting shadows on the wall, represents the flickering light of partial truths—those impressions and beliefs that are shaped by the senses but lack the substance of true understanding.

Aristotle’s response—that the journey upward mirrors the soul’s ascent into the realm of the intellect—is as perceptive as it is profound. To glimpse the Good is not merely to see but to know, in the fullest sense, the source of all that is true, beautiful, and rational. It is the culmination of the philosopher’s quest, the point at which the eternal becomes not just an idea but a lived reality.

Yet, this ascension brings with it a burden, does it not? The freed soul, now in communion with the eternal, faces a choice: to remain in the light or to descend once more into the cave, bearing the responsibility to illuminate the shadows for those still bound. Plato’s prisoner, now transformed into a philosopher, must grapple with this tension—between the allure of the changeless reality above and the duty to guide others trapped below.

So, I ask you, Platohagel: if the philosopher’s task is to bridge these worlds, how does one balance the love of the eternal with the demands of the temporal? Is the philosopher, by nature, a solitary figure, or is their fulfillment tied to their willingness to descend and serve?