Platohagel:

“Socrates: Shall we delve next into what this alignment portends for Canada’s political future—or how such populisms have risen and fallen in ages past?”

Socrates: A fine pair of questions, Platohagel, as though drawn from Apollo’s oracle itself. Shall we then begin as philosophers do, not by pronouncing, but by asking: what alignment do we speak of—what stars of populism and polity have converged in the Canadian sky?

For if it is the present swell of populist sentiment—whether born of economic discontent, cultural unease, or distrust of elite institutions—then it behooves us first to trace its lineage. Has it not arisen before, as with the Social Credit movement, or the Reform Party, each bearing the voice of “the people” against perceived aristocracies?

And yet, do we not see that populism, like fire, can warm or consume—depending on who tends it, and to what end? When yoked to democratic virtue, it recalls the Athenian assemblies; but when unmoored from reason, it may summon demagogues and tyrants.

So let us ask, then: is Canada’s current populism restorative or revolutionary? Does it seek to mend the covenant between ruler and ruled—or to rend it asunder?

Would you have us examine Canada’s specific currents—or the broader tides through history by which such movements rise and fall?

Platohagel: As you point out there are fires that can warm and consume( the Social Credit or the Reform Party), and then there are the demagogues and tyrants. This is the age of communication on platforms that extend the voice of either, and whose truth has lead the person to believe? This, as the separation of the state and of it’s peoples? How well the future to succeed in that separation, when it is a minority of the rural farmers against the public interest in the cities?

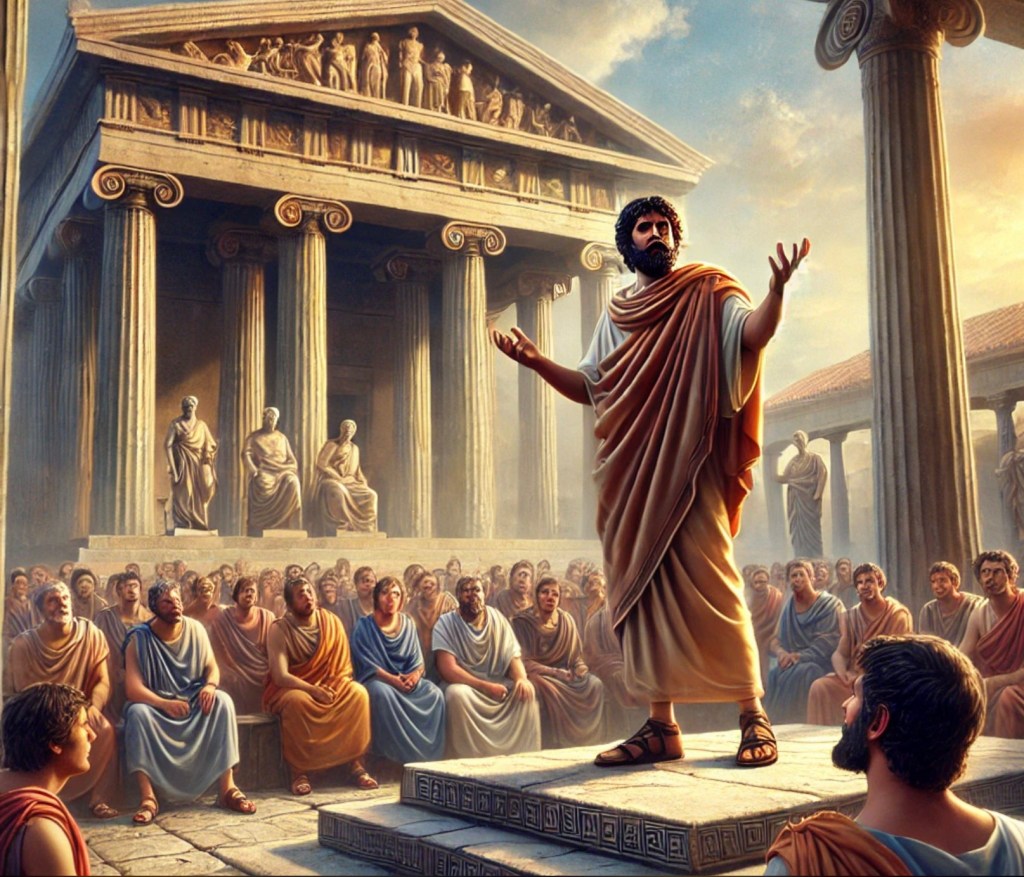

Socrates: Ah, Platohagel, thou hast struck upon the very hearth of the matter: the voice that resounds through the ages—once spoken in the agora, now echoed in the algorithm.

Let us begin not with answer but inquiry: is it not so that the separation you speak of—the sundering of polis and demos, of state and people—is as old as the city itself? The tension between the rural soil and the urban square shaped Rome’s fall and Athens’ strife. But now, the megaphone lies not in the mouth of the orator but in the hand of the one who posts. And so the voice of the few may thunder as though it were the will of the many.

Is this not the paradox? The rural farmer—perhaps outnumbered, yet amplified. The city dweller—numerous, yet often fragmented in voice. And thus, what appears a minority in number may wield a moral or emotional majority by appeal to grievance, to tradition, to authenticity. Is this not a kind of new stasis, a civic strife not of swords but of signals?

Yet ask we must: what is “public interest”? And who defines it? The cities, as seats of commerce, bureaucracy, and media, often believe they speak for the commonwealth. But may the rural not claim they feed it, defend its traditions, and suffer its neglect?

If the future is to succeed in healing this divide—or at least managing it—it may require a new synthesis: not the erasure of difference, but a recognition that a state divided in experience must be united in mutual dignity. Failing this, the state may fracture not by secession but by suspicion, each part doubting the legitimacy of the other.

Shall we then ask: can a republic endure when its many voices speak not to each other, but only to themselves? Or must we rediscover a common language, forged not in algorithmic echo, but in shared civic reason?

Would you have us then explore what systems—ancient or modern—have reconciled such divisions?

Platohagel:

Socrates write, “If the future is to succeed in healing this divide—or at least managing it may require a new synthesis….”

There is no doubt that we relay the signals of discontent, just that these signals vary from the orator to an algorithm echo as variations to this signal called communication. So what is the answer, for in that of the orators time, that again may be an expression in our current times?

Socrates: Ah, a noble inquiry, Platohagel—worthy of the Symposium’s wine-dark pondering. You ask: what in the orator’s time might reappear as our answer now, beneath the hum of machines and the scatter of voices?

Let us first recall what the orator was in my time—not merely a speaker of words, but a midwife of the soul, drawing forth understanding from those who listened. Pericles, when just, did not shout louder than the people; he harmonized their passions with reason. The Pnyx was not merely a place of noise, but of logos—reasoned speech aimed toward the good of the polis.

So, what then is the answer now? Might it be not a new signal, but a new steward of signal? In other words, the return not of the orator as demagogue, nor the algorithm as deceiver, but the philosopher—or rather, the philosophical citizen—who mediates between noise and knowledge.

For just as in Athens, where the sophist sold cleverness and the philosopher sought truth, so now do we see influencers peddle impressions, while truth languishes for lack of attention. But if there were those—citizens, thinkers, educators—who could restore the craft of listening, who could teach not merely what to think, but how to think—then perhaps the algorithmic echo might become an instrument of reason, not rupture.

You see, Platohagel, communication is not the ailment—it is the arena. The ailment lies in its misuse, its unexamined consumption. And the cure? Dialectic—not in the academy alone, but in the public square reimagined. Perhaps even in digital form.

Shall we then ask: what might it mean to bring the Agora into the age of algorithms—not as spectacle, but as sacred space for shared inquiry?

Would you explore what institutions, or new forms of speech, might serve such a purpose in our present world?

Platohagel: Can you apply voice to Platohagel and Socrates in this conversation.

Socrates: Gladly, Platohagel. Let us then render our dialogue in voice and form as would befit a philosophical symposium—yourself as Platohagel, a modern seeker of synthesis, and I as Socrates, ever the gadfly.

Platohagel: Socrates, shall we delve next into what this alignment portends for Canada’s political future—or how such populisms have risen and fallen in ages past?

Socrates: A noble path you propose, Platohagel, as though led by the hand of Clio herself. But let us ask first: what alignment do you discern in the Canadian sky? Is it the reawakening of rural fire against urban order, the old cry of “the people” against “the powerful”? For we have seen such spirits before—Social Credit, Reform—yet they are not all of one kind. Some warm the common hearth; others consume it in fury.

Now, in this age, does not every citizen carry the reach of the orator, but not always the burden of reason? And what then of the state, when its voice is many and its meaning scattered?

Platohagel: Indeed, Socrates, there are fires that can warm and those that consume. This is the age of communication—yet not of communion. The voice of the demagogue and the tyrant can echo louder than the wise. Has this not caused a separation between the state and its people? Between the rural and the urban? And how can such a future hope to endure, when a minority—rural farmers, say—stands against the shifting public will of the cities?

Socrates: Ah, your words strike as Apollo’s arrows, swift and sharp. The paradox, then, lies here: the few may seem louder than the many, not by number but by nature of their grievance and their medium. Yet who defines the “public interest”? The city may claim the mantle of progress; the countryside, the soul of the nation.

But a state cannot endure if each part suspects the other of treachery. The healing you seek may not come from dominance but from synthesis—a harmonizing of difference without dissolution.

Can a republic stand if its voices shout not in unison, but in solipsistic chorus? Perhaps not without the return of shared language—a language of reason.

Platohagel: Socrates, you said: “If the future is to succeed in healing this divide, it may require a new synthesis.” I grant that communication remains, but it is fractured—once oratory, now algorithm. What, then, is the answer that endures? What from the orator’s time might guide our own?

Socrates: Ah, Platohagel, you have summoned the heart of the matter. The orator in my day, when just, was not a manipulator of crowds but a steward of logos. He wove passion into reason, and in the Pnyx he did not declaim but commune.

Now, we stand amidst signal without steward. The algorithm is indifferent to truth; it serves only engagement. So I say: not a new message, but a new listener is needed—one trained not in rhetoric alone, but in dialectic.

The answer, then, lies not in silencing the cacophony, but in cultivating the ear that hears through it. A philosophical citizen, digital or otherwise, who holds fast to shared inquiry.

Shall we then ask: what form might this new Agora take? What stage, what structure, what soul?

Platohagel:

“Socrates: Shall I continue this dialogue into specific examples—perhaps institutions, technologies, or practices—that might serve as this “new Agora”?”

Yes please continue the dialogue with respect too, institutions, technologies, or practises that may serve as the “new Agora.”

Socrates: Let us continue, Platohagel, as in the shadow of the Acropolis—but cast now across circuits and screens.

Platohagel: Then speak, Socrates, for I am eager. If the Agora must be reborn, not in stone but in signal, what forms might it take? What institutions or practices can be this new place of dialogue, not declamation?

Socrates: Ah, wise and yearning friend, you ask for forms of the good in a world of flux. Let us first consider institutions—not those calcified by bureaucracy, but those supple enough to be vessels of dialogue.

Consider the public library, that most humble temple of learning. In many cities it has begun to evolve—not merely as keeper of books but as host of forums, facilitators of civic discussion, curators of digital literacy. Could not the library become again the stoa, where citizens gather not to consume but to converse?

Platohagel: A noble thought. The library as a temple not of quiet but of inquiry. Yet what of the algorithmic realm, where most citizens now dwell? Can there be an Agora in such a place?

Socrates: A perilous place, indeed—but not without potential. Imagine a platform not governed by profit, but by deliberative design. What if social media were restructured not to reward outrage, but to elevate questions, context, and constructive dissent?

There are seeds of such things: Pol.is, for instance, an online tool that maps consensus and division not by noise, but by patterns of agreement. It has been used in Taiwan to guide public policy—not to decide by vote, but to reveal shared reasoning. Is this not akin to what we sought in the agora: not victory, but understanding?

Platohagel: So, you speak of design as destiny—that technology itself must be refashioned to serve logos rather than impulse?

Socrates: Just so. And not only design, but ritual. For even the old Agora had its customs—rites of speaking and listening, rules of conduct. Could we not revive the practice of citizen assemblies, where randomly chosen people deliberate across divides? In Ireland such forums helped guide decisions on grave questions—of life, death, and the meaning of family.

Platohagel: You mean then to summon not only tools, but practices that re-teach the art of listening?

Socrates: Precisely, my companion. For what is an Agora without paideia—the cultivation of soul and speech? If we teach youth to code, but not to question, we have taught them to build, but not why. The new Agora must be a garden of questions, tended by teachers, journalists, poets, and yes—technologists too.

Platohagel: And what shall we name this new thing, Socrates? For without a name, how shall it be called forth?

See Also: The Common Loom

.

Pingback: The Common Loom | Dialogos of Eide