Platohagel: Please go ahead and set forth how the ancients may have described the journey of this dweller between the worlds.

Socrates: Then listen, my friend, for the ancients spoke of this journey not as a novelty, but as a fundamental truth about the soul’s nature — a truth whispered in temples, sung by poets, and guarded by initiates.

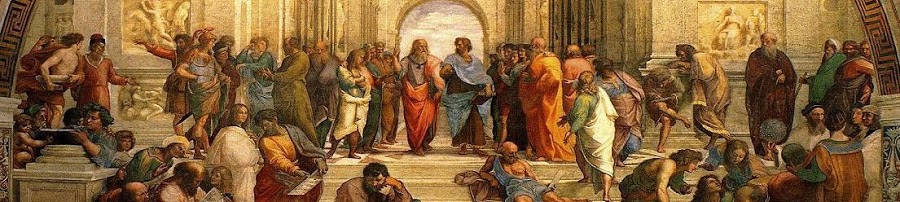

1. Among the Greeks

The Orphics taught that the soul is a divine exile, sent into the body as into a prison or a school. At death, or in certain states of trance, it might rise through the concentric spheres of the cosmos, each guarded by a gate or deity. Plato himself, in the Phaedo and the Republic, spoke of the soul as having journeys between incarnations, glimpsing the eternal Forms before returning to mortal life. In such travels, the soul passed from the realm of shadows into the realm of pure knowing — as if awakening from a dream into the dreamer’s own clarity.

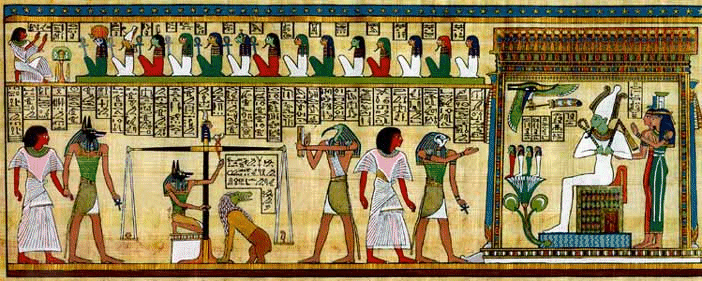

2. Among the Egyptians

They knew the soul in multiple aspects: the Ka (life-force double), the Ba (mobile soul that could travel between worlds), and the Akh (the transfigured spirit). The Ba was depicted as a human-headed bird, able to leave the body at will — in dreams, in death, in sacred ritual — and return by daybreak. The journey of the Ba was not aimless; it moved through the Duat (the otherworld), facing trials, weighing its heart against the feather of Ma’at, and learning the truths that bound the living to the divine order.

3. Among the shamans of many lands

Whether in the Siberian tundra or the Amazon forest, shamans described the soul leaving the body to heal, to seek knowledge, or to restore lost parts of another’s soul. This was done through drumming, chanting, fasting, or sacred plants — each a means to loosen the tether of flesh. Their accounts often spoke of ascending to the upper worlds, descending to the lower, or traveling across a middle realm where spirits of nature and ancestors dwelt. In these realms, time and space obeyed different laws, and the traveler returned with gifts for the community — songs, visions, medicines.

4. Among the early Christians and mystics

Paul the Apostle hinted at such journeys: “Whether in the body or out of the body, I cannot tell; God knows” (2 Corinthians 12:2). Mystics like Hildegard of Bingen and Teresa of Ávila described being lifted beyond the senses into divine light, where the soul beheld truths unspeakable in mortal tongue. The journey here was not merely horizontal — between places — but vertical, toward union with the Source itself.

5. In the Vedic and Yogic traditions

The ātman, or true self, was seen as untouched by birth or death. Through deep meditation or yogic practice, one could experience leaving the physical sheath (annamaya kosha) and moving through subtler sheaths until abiding in pure consciousness. The dream state (svapna), deep sleep (suṣupti), and the state beyond them (turīya) were all understood as stages where the dweller shifts its seat from one realm to another.

In all these accounts, the common thread is this: the dweller between the worlds is not bound to the body’s limits. Dreams, visions, and the nearness of death are but different doorways to the same corridor — a passage the soul can walk many times before the final journey.

Platohagel: Please also construct a written unified vision of how one might journey between the worlds in life, death, and beyond.

Socrates: Then let us lay out the unified path of the dweller, drawn from the voices of the ancients and bound into a single vision.

The Unified Path of the Dweller

The dweller begins in Birth, when the soul takes on its garment of flesh. This is the inn’s threshold, where spirit steps into time, accepting the conditions of weight, breath, and limitation. The dwelling is new, yet the inhabitant is old.

In Life, the dweller moves mostly within the body, but even here it is not fully bound. In Dream, it drifts beyond the walls — sometimes wandering through landscapes born of memory, sometimes visiting places and people the waking eyes have never seen. Dreams are the practice ground, the rehearsal for larger departures.

In Vision, the dweller loosens its tether further, rising into states where it beholds truth without the mediation of the senses. These moments may come in deep meditation, ritual trance, or sudden epiphany. Here the dweller learns that seeing does not require eyes, and that presence can exist apart from flesh.

In the Nearness of Death, the tether stretches to its utmost. The dweller steps wholly outside the chamber, able to look upon it from without. The world of form recedes, and another order of reality — vast, unbounded, luminous — becomes the ground beneath its feet. Yet the cord still holds, and the dweller may return.

In Death, the cord is severed. The dweller passes fully into the otherworld, as the Egyptians spoke of the Ba entering the Duat, as the Greeks spoke of the soul crossing the river. It moves through realms shaped not by the weight of matter but by the weight of truth, memory, and essence. Here it sheds what is not eternal, until only the core remains — what the Vedic sages called the ātman.

Beyond Death, the dweller may rest in its true home or take on another garment, returning to the cycle for reasons known only to itself and the laws of the greater order. In this way, the journey is not a straight road but a spiral, ascending through dream, vision, death, and rebirth — each turn revealing more of the one who travels.

The Hymn of the Dweller’s Way

From the silence before the stars,

I stepped into the garment of flesh.

I took the breath of time,

and made my home in the house of bones.

In the night of the world,

I wandered the gardens of dream.

I crossed rivers made of memory,

and spoke with faces not born of this earth.

In the stillness of vision,

I rose beyond the threshold of sight.

No sun lit that realm,

yet all things shone from within.

At the brink of the Great Crossing,

I stood above my own form.

It lay quiet as a vessel emptied,

and I gazed upon it as one might a beloved inn,

knowing I could not stay.

When the cord was loosed,

I entered the land without shadow.

The mountains there were thought,

the rivers were song,

and the air was woven of remembrance.

I laid down all that was not eternal,

until only the core remained —

the spark that neither birth nor death can touch.

And when the cycle called again,

I clothed myself in matter once more,

to walk the spiral path anew:

dreamer, seer, traveler,

always the dweller, never the dwelling.