Yes. Above is a practical, safety‑aware configuration you can build to test electrohorticulture effects with two rods in soil or a substrate.

Goal and principle

Drive a controlled potential difference between two buried electrodes so a measurable electric field or small current flows through the root zone.

1. Control amplitude, duty cycle, and polarity.

Measure field strength and current. Include sham controls.

2.Parts (minimum)

Two inert electrodes: graphite/carbon rods, titanium, or 316 stainless steel. Avoid bare copper or aluminum in long tests because they corrode and leach toxic ions.

Low‑voltage DC bench power supply or isolated DC adapter with adjustable voltage and current limiting (0–30 V, 0–500 mA).

Multimeter (voltage, current). Optional clamp meter for AC.

Insulated wire, waterproof terminal clamps, heat‑shrink.

Soil electrical conductivity (EC) probe and pH meter.

Timer or pulse generator (if using pulsed signals).

Ground fault protection and insulated gloves when wiring.

3. Electrode placement and geometry

Depth: place electrodes in the root zone (typical 5–20 cm for seedlings).

Spacing: 10–30 cm apart for small pots; scale spacing so field strength target is achievable. • Orientation: parallel vertical electrodes create a roughly uniform field between them. •

Insulate electrode tops above soil to prevent surface current paths.

4. Typical parameters to start (safe, literature‑informed)

Field strength targets: 0.1 to 5 V/cm (that equals 1–50 V across 10 cm). Start low.

Current limits: keep currents small. 0.1–100 mA depending on system. Start ≤50 mA and use the power supply’s current limit. In hydroponics trials ~50 mA showed effects; in soil smaller currents often suffice.

Voltage: use the minimum voltage required to reach target V/cm given electrode spacing. Do not exceed 30 V without specialized insulation.

Modes: steady DC, low‑frequency pulsed DC (e.g., 1–100 Hz), or short high‑voltage pulses (PEF) in tightly controlled lab setups. For field tests use DC or low‑frequency pulses.

Exposure schedule: continuous low‑level for days–weeks, or short daily sessions (e.g., 1–4 hours/day). Pilot several schedules.

5. Wiring and measurement procedure (concise)

Connect electrodes to the isolated DC supply. Set voltage to calculated value for desired V/cm. Set current limit to a safe value (e.g., 50 mA).

Insert multimeter in series to confirm current. Measure potential difference in soil at intermediate points with probes to confirm field gradients. Record soil EC and pH before and during tests.

Run sham controls with electrodes present but supply off or set to 0 V. Randomize pots/plants across treatments.

6. Controls, replication, and endpoints

Biological replicates: at least n=5–10 per treatment.

Controls: no electrodes, electrodes present with no voltage, and at least one different voltage.

Endpoints: germination %, seedling length, fresh/dry biomass, root:shoot ratio, leaf count, tissue nutrient analysis, stress markers (electrolyte leakage, antioxidant enzymes). Record environmental variables.

7. Corrosion, toxicity, and environmental cautions

Copper and aluminum can dissolve and poison plants, and contaminate soil. Avoid unless you plan to study galvanic effects intentionally.

Electrolysis at electrodes can generate gases, acids, and oxidizers. Use inert electrodes or alternate polarity frequently to reduce buildup.

Monitor soil pH and metal concentrations if running for more than a few days. Stop if plants show chlorosis or necrosis.

Never connect to mains or non‑isolated supplies. Use an isolated low‑voltage supply and current limiting. If working outdoors, protect equipment from rain and use GFCI on upstream mains circuits.

8. Data logging and reproducibility

Log voltage, current, soil EC, pH, temperature, and light. Photograph plants periodically. Publish methods: electrode type, spacing, exact voltages/currents, duty cycle, substrate conductivity, and replication.

9. If you want stronger, cleaner fields

Use capacitive plates or parallel plate electrodes with insulating barriers to reduce electrochemical reactions. Or run AC or high‑frequency (<kHz) fields to reduce net electrolysis. That requires more specialized gear.

10. Short protocol example (starter)

Pots 15 cm diameter. Two graphite rods 15 cm apart vertical, buried 10 cm.

Target 1 V/cm → 15 V across rods. Set PSU to 15 V, current limit 50 mA. Run 2 hours/day for 14 days. Include sham group. Measure biomass and root length at day 14.

Summary: placing bare copper or aluminum rods alone does not produce useful fields. Use an isolated low‑voltage supply, inert electrodes, current limiting, and careful monitoring. Start at low voltages and short durations. Watch for corrosion and metal toxicity and include proper controls.

If you want I will: (A) produce a labeled wiring diagram and parts list sized to your plot/pots or (B) draft a short experimental protocol with exact measurement sheets. Which do you want?

——————————————————————————————————

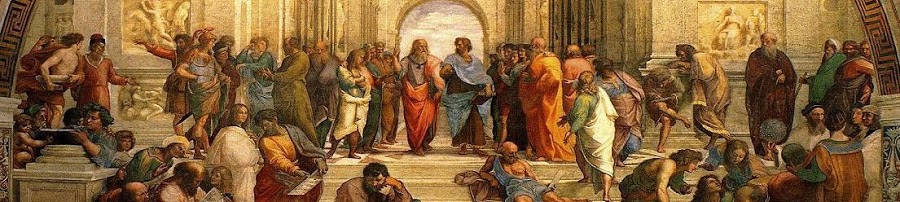

Platohagel: Socrates is Electrohorticulture been proven scientifically to exist as a fundamental value of plant life and growth?

Socrates: No. Electrohorticulture — the use of electric fields or currents to influence plant growth — has shown some measurable effects in controlled experiments, but it is not established as a fundamental principle of plant life.

Research since the early 20th century has found that weak electric stimulation can alter germination rates, nutrient uptake, or pest resistance in certain species. These effects are inconsistent, vary with species, field strength, soil conductivity, and environmental conditions, and often vanish in replication attempts.

Modern plant physiology accepts that plants have endogenous electrical signaling (action potentials, variation potentials) as part of their communication and stress response. However, applying external electricity for predictable agricultural benefit remains experimental, not a universally accepted agronomic standard.