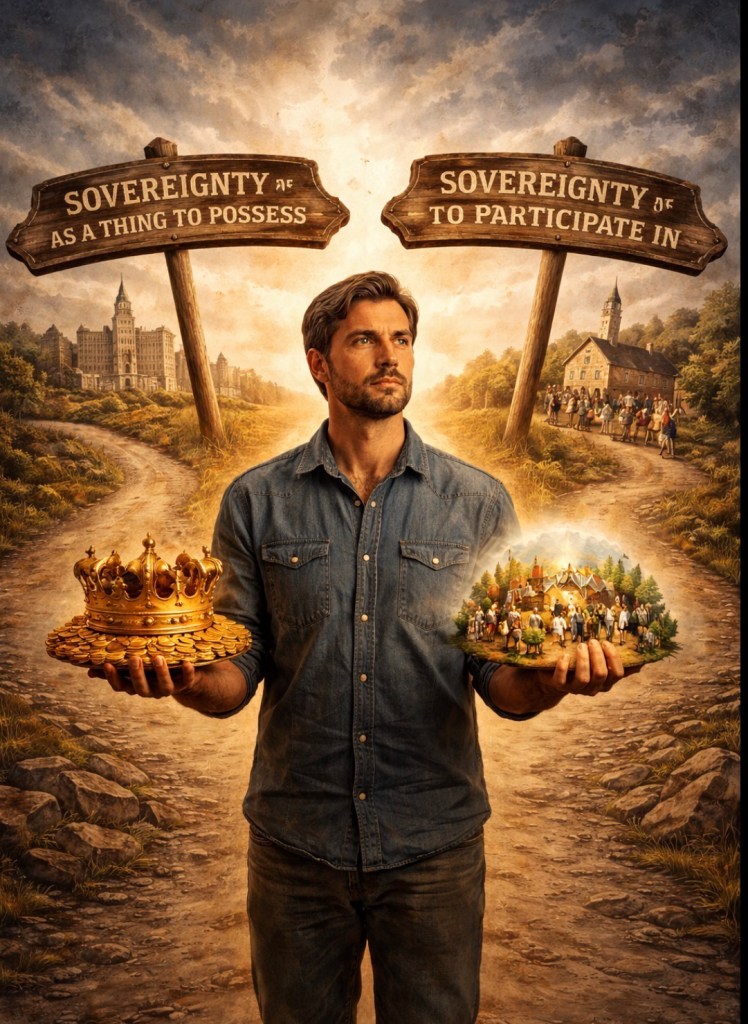

Tell me first: if sovereignty were something one possesses, like land or gold, where would it reside? In a document? In a parliament? In the hands of those who govern? And if so, how could it ever be lost without force?

Yet we observe that sovereignty does vanish without armies crossing borders. It fades when laws are obeyed only from fear, when offices retain authority but lose legitimacy, when citizens speak of “the state” as if it were an occupying power rather than their own reflection. Nothing was seized—yet everything changed.

This suggests a contradiction. What can be lost without being taken was never truly possessed.

Now consider sovereignty as something one participates in. Participation requires:

• shared belief,

• reciprocal obligation,

• continual renewal.

It lives not in institutions alone, but in the daily consent of those who recognize one another as members of a common order. Here, sovereignty is not a thing, but a relation

“When trust in national institutions weakens, the question of sovereignty descends:

• From nation → province

• From province → community

• From community → household

• From household → individual conscience”

When participation weakens, sovereignty descends—not because it is stolen, but because it seeks a lower level where trust still exists. From nation to province. From province to community. From community to family. From family to the solitary conscience.

This descent is not rebellion at first; it is conservation. The citizen withdraws loyalty upward only to preserve meaning inward.

Thus entire nations quietly turn not at moments of revolution, but at moments of withdrawal.

So we arrive at the answer, though it does not arrive loudly:

Sovereignty is never possessed.

It is continuously practiced.

And when a people forget how to practice it together, they do not become free—they become alone.

See Also: Counter-views Within Families

Pingback: The Counter-views Now Appear Within Families | Dialogos of Eide