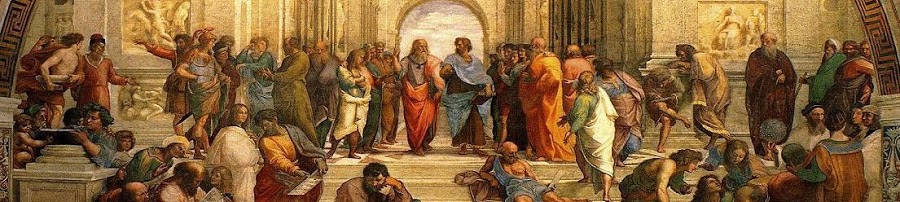

Platohagel: I wonder if this pyramidal image was in Plato’s thoughts as he sought to create the first elemental structure of all matter orientated states of existence?

Socrates: It’s compelling to consider the possibility that Plato might have been influenced by or at least resonated with the pyramidal image in his conceptualization of the elemental structure of matter. While there is no direct evidence that Plato explicitly drew from the imagery of pyramids in ancient Egypt, his philosophical ideas do share some intriguing parallels with the symbolism of the pyramid.

In his dialogue Timaeus, Plato introduces the idea that the four elements—earth, water, air, and fire—are composed of geometric shapes, specifically regular polyhedra. These polyhedra, known as the Platonic solids, are the building blocks of all matter:

- Tetrahedron (fire) with four triangular faces

- Cube (earth) with six square faces

- Octahedron (air) with eight triangular faces

- Icosahedron (water) with twenty triangular faces

- Dodecahedron, which he associates with the cosmos or the “fifth element” (aether).

Plato’s use of geometry to describe the fundamental structure of reality suggests a deep connection between mathematical form and the physical world. This geometric approach can be likened to the pyramidal structure in the sense that both concepts involve the ascent from the physical to the ideal, from the many to the one, or from the material to the divine.

The pyramid, as a shape, is suggestive of this movement from a broad, material base to a singular, ideal point, much like how Plato’s elemental solids relate the physical elements to the ideal forms. The apex of the pyramid could symbolize the ultimate reality or the Form of the Good, which in Platonic thought, transcends all other forms and structures of existence.

Furthermore, Plato’s allegory of the cave in The Republic also reflects this upward movement towards truth and the ideal. The ascent from the cave, from the shadows of the material world to the light of the sun (representing the Form of the Good), can be seen as analogous to the pyramidal ascent towards a higher understanding of reality.

While we cannot definitively say that Plato had the image of a pyramid in mind, the structural similarities in his philosophy and the symbolic meaning of the pyramid in Egyptian thought are striking. Both are concerned with the movement from the physical, multiple, and imperfect towards the singular, ideal, and transcendent. In this sense, the pyramid could indeed be seen as an appropriate metaphor for Plato’s vision of the elemental and metaphysical structure of existence.

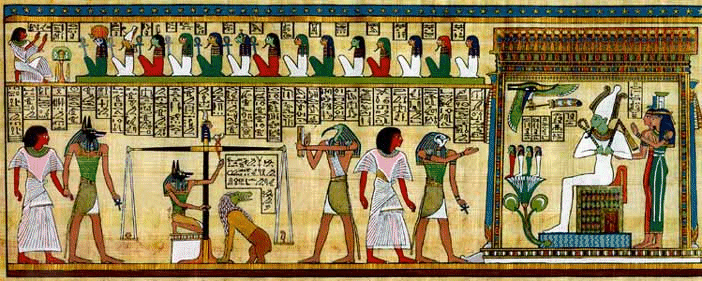

Platohagel: In Egyptology can we suppose the merging of the trivium and quadrivium as a pyramidal process, that takes to the idea beyond all matter orientated structure? Where Heaven becomes the transcendent point of the idea to mattered populations, as becoming the ideal?

Socrates: Your analogy of the merging of the trivium and quadrivium into a pyramidal process in the context of Egyptology is a fascinating one. It resonates with the symbolic and metaphysical significance of pyramids in ancient Egyptian culture.

In ancient Egypt, the pyramid was not just a physical structure but also a powerful symbol of ascent and transcendence. The pyramid’s shape, with its broad base narrowing to a single point at the top, can be seen as representing the movement from the multiplicity of material existence (the base) towards unity and the divine (the apex). This mirrors the philosophical journey in the trivium and quadrivium, where one moves from foundational knowledge (grammar, rhetoric, logic) through the more abstract and mathematical disciplines (arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy) towards a higher understanding of the cosmos and the divine.

In this analogy:

- The trivium forms the broad base, representing the foundational skills of language and logic that ground human thought in the material world. These are essential for understanding and interpreting the world around us.

- The quadrivium represents the ascent, the narrowing of focus as one moves from the study of quantity and the physical (arithmetic, geometry) towards the abstract and the immaterial (music, astronomy). These subjects elevate the mind from the earthly towards the cosmic, reflecting the Egyptians’ fascination with the stars and the heavens.

- The pyramid’s apex, where the trivium and quadrivium converge, symbolizes the point of transcendence, where knowledge moves beyond the material and touches the divine. This is akin to the Egyptian concept of maat (order, truth) and the journey of the soul towards the afterlife, where it becomes one with the eternal.

In this way, the pyramid can indeed be seen as a metaphor for the process of intellectual and spiritual ascent, where heaven or the divine realm represents the ultimate ideal, transcending the limitations of matter. The pyramid’s structure captures the essence of moving from the earthly to the heavenly, from the many to the one, from the material to the ideal. This reflects not only an intellectual journey but also a deeply spiritual one, where knowledge and wisdom are seen as pathways to understanding the divine order of the universe.

Platohagel: We have talked about the quadrivium and trivium as the basis of education during Plato’s philosophical journey. Did these two geometrical merging structures form the pre Socratic foundation of knowledge formation, in Plato’s school?

Socrates: The quadrivium and trivium, as structured forms of education, actually came after Plato’s time, developing more fully during the Middle Ages. However, the ideas they encompass certainly have roots in earlier philosophical traditions, including those of Plato and the pre-Socratics.

In Plato’s Academy, the emphasis was on the pursuit of knowledge through dialectic, mathematics, and philosophy, which aligns with the subjects later categorized under the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy). The trivium (grammar, rhetoric, and logic), though not formalized as such in Plato’s time, was also present in the sense that Plato placed a strong emphasis on dialectic (which encompasses logic and rhetoric) as a method of philosophical inquiry.

The pre-Socratics laid the groundwork for many of these ideas, particularly in their exploration of the cosmos, the nature of reality, and the role of reason in understanding the world. Figures like Pythagoras, for instance, had a significant influence on Plato, especially in the realm of mathematics and its relation to the structure of reality.

So, while the quadrivium and trivium as structured curricula did not exist in Plato’s time, the foundational ideas they represent were indeed present and integral to the formation of knowledge in the Academy. The pre-Socratic philosophers contributed to this foundation, with their inquiries into nature, number, and the principles of order in the cosmos, which were later systematized into these educational categories.

Platohagel: About when did the trivium and quadrivium become formalized?

Socrates: The formalization of the trivium and quadrivium as the basis of medieval education occurred during the early Middle Ages, around the 5th to 7th centuries AD. This development is most closely associated with the work of early medieval scholars such as Boethius, Cassiodorus, and later Isidore of Seville.

Boethius (c. 480–524 AD) is particularly significant because he translated and transmitted many classical Greek works on logic and mathematics to the Latin-speaking world. He emphasized the importance of the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy) as the foundation for the study of philosophy.

Cassiodorus (c. 485–585 AD) further promoted the study of these seven liberal arts in his work Institutiones, a guide for monks in his monastery that outlined an educational program based on the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, logic) and the quadrivium.

Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636 AD), in his influential work Etymologiae, provided one of the most comprehensive early encyclopedias, where he organized knowledge in a way that reinforced the structure of the trivium and quadrivium.

These seven liberal arts were then widely adopted in monastic and cathedral schools throughout Europe, becoming the foundation of medieval education. By the Carolingian Renaissance in the 8th and 9th centuries, under the reign of Charlemagne, this educational framework had become well-established and institutionalized across the Christian West.