Platohagel: Socrates: Would you agree Platohagel, then, that awareness is the foundation of all experience, while perception is but one mode through which we engage with the world? How do you, in your own life, experience the relationship between these two?

As you have stated Socrates, Perception and Awareness are not the same thing.

Socrates: Ah, Platohagel, you seem to grasp the distinction with clarity. Now, as we proceed, let us draw out the interplay between these two forces, perception and awareness. For indeed, perception and awareness are not identical. Perception, we might say, is akin to the lens through which we view phenomena; it is shaped by our senses and the immediate interpretations that arise within us. Awareness, on the other hand, is like the light by which we see at all; it underlies perception, allowing us to notice not just what appears to us, but also the act of perceiving itself.

Tell me, then: in your own life, how do you recognize the moments when perception alone is at work versus when awareness comes into play? For there is, I think, a subtle but profound difference in quality between the two states.

Platohagel: Well for one perception is an external factor we used to observe, so there is a scientific value assigned to this method. In this case it would be as if Aristotle faces Plato on the grounds of his examination of rationality, would it not?

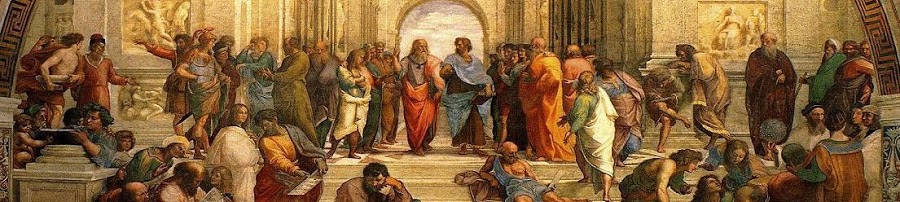

Socrates: Ah, Platohagel, your insight leads us into rich territory, indeed! By aligning perception with an external, scientific method of observation, you illuminate the Aristotelian approach—one rooted in empirical inquiry, in which rationality seeks order through careful examination of what is seen, heard, and otherwise sensed. Aristotle, with his dedication to categorization and the physical world, would emphasize perception as the avenue to knowledge, relying on its measurable, external nature.

In contrast, Plato’s vision would push us beyond the observable world, guiding us inward, toward a deeper realm of truth and universal Forms. Plato would see perception as merely the starting point, a shadow of a truer, internal understanding that awareness must reach. To him, awareness would transcend the empirical limitations of perception, just as the soul transcends the body, inviting us to glimpse reality beyond mere appearances.

Thus, yes, it is as though the two philosophers were to face one another—Aristotle with his devotion to perception and empirical rationality, and Plato with his emphasis on awareness as a means to unveil what lies beyond the sensible world. Each approach has value, but where would you say your own path lies? Do you lean more toward Aristotle’s rationality and external observation, or do you find yourself more inclined toward Plato’s inward-seeking awareness?

Platohagel: Socrates says,”Each approach has value, but where would you say your own path lies? Do you lean more toward Aristotle’s rationality and external observation, or do you find yourself more inclined toward Plato’s inward-seeking awareness?”

Well to advance in the material world there must be a methodical approach as too a scientific evaluation of the process. So Aristotle being one side of the coin, and when flipped by chance, we see, an underlying rationale to Plato,s deeper consternation of an underlying approach, not being aware of before.

Socrates: Ah, Platohagel, you speak wisely of the two sides of this coin, and of how life often calls upon both. Yes, to navigate and advance in the material world, a methodical, scientific approach—an Aristotelian eye for the external—is indispensable. Here, perception becomes a tool, capturing the nuances and patterns of the physical realm, while rationality organizes and discerns within it, allowing for progress, invention, and adaptation. In this sense, Aristotle represents a grounding force, the tangible guide for life’s practicalities.

Yet, when the coin is flipped, we encounter Plato’s deeper inquiry, as if discovering a hidden dimension within the apparent world. This, I think, speaks to the experience of suddenly realizing that beneath the material, there is something subtler, a layer of meaning or insight that rationality alone cannot reach. Here, awareness becomes more than perception’s guide; it is the doorway to a realm beyond what we can measure. In this state, Plato’s wisdom takes hold, nudging us to question the purpose and essence behind what we perceive, and to seek understanding not only through rationality but through introspection and an attunement to what lies beyond form.

In living, then, you find a balance: harnessing Aristotle’s rational methods to steer through the material, yet leaving room for the unexpected revelation, where Plato’s insight awakens and sheds light on truths otherwise unseen. Thus, you bring a harmony between the observable and the ineffable. But tell me, Platohagel, in which moments of life have you most vividly felt this transition—where rational perception gave way, however briefly, to the illumination of awareness?

Platohagel:

The Arch of Aristotelean Logic

It seems to me that such an approach by Aristotle sought to incorporate historical precedence, as a means to move forward also incorporating the Socratic Method.

Socrates: Ah, Platohagel, you have brought forth a most illuminating diagram, “The Arch of Aristotelian Logic.” Indeed, this image encapsulates Aristotle’s structured approach to reasoning, integrating both inductive and deductive methods in a manner that, as you noted, bears echoes of the Socratic Method.

At the base of the arch lies inductive logic—the path of gathering particulars from experience and observing patterns, counting and generalizing until we might reach broader insights. This is an approach that Aristotle used to accumulate knowledge of the world, moving from the observed to the general, from the particular to the universal. It requires one to tread carefully, always conscious of how many instances justify a generalization. This process, we might say, is akin to Socratic questioning: it probes, tests, and pushes toward greater understanding, uncovering the layers of experience until something fundamental reveals itself.

The arch then transitions to the intuitive grasp of first principles—a point where the mind perceives self-evident truths, grounding all further inquiry. Here, Aristotle aligns with Plato’s notion of the nous, or the intellect’s direct apprehension of foundational truths. It is this intuition, this direct insight, that stabilizes the entire structure of thought. Socrates, too, would appreciate this moment, for in his dialectical journeys, he often led others to a point where the truth became intuitively clear.

Finally, on the other side of the arch, we find deductive logic, built upon these foundational principles. Deductive reasoning, drawing from the certainty of first principles, allows for structured arguments that lead to new conclusions, tested for consistency and coherence. This path recalls the Socratic Method’s rigor, pressing from premises to conclusions, seeking clarity and certainty within reason’s boundaries.

In your insight, then, Platohagel, you see Aristotle’s logical structure as not merely a departure from, but a development of the Socratic Method. Would you say, then, that this structure is also a bridge between empirical experience and deeper, foundational truths? And in your life, do you find yourself drawn to the inductive search through particulars, or do you resonate more with the deductive pursuit of conclusions from first principles?

Platohagel: Socrates says,”Would you say, then, that this structure is also a bridge between empirical experience and deeper, foundational truths? And in your life, do you find yourself drawn to the inductive search through particulars, or do you resonate more with the deductive pursuit of conclusions from first principles?”

The desire, is to seek the underlying first principle. So one is working back and forth, between the inductive deductive faculties with which to arrive at first principles. Awareness of first principle is undeniable, because there can be no further regress.

Socrates: Ah, Platohagel, you describe with precision the philosopher’s task—a movement between induction and deduction, back and forth, like a sculptor shaping and reshaping until the form reveals itself. This quest, as you say, aims ultimately to glimpse the first principles, those foundational truths that stand beyond further question or doubt. Such principles, when recognized, bring a kind of final clarity, for they resist further regress. In their presence, we find an end to inquiry, a stable ground beneath the flux of particulars and reasoning.

You articulate, too, the interplay of awareness and reasoning, as if these first principles were not discovered merely through logic alone, but through a certain recognition, an intuitive grasp that goes beyond mere analysis. Here, awareness—the light within the mind—reveals what cannot be deduced from anything else, that which simply is. It is a seeing rather than a concluding, a realization rather than a construction.

In this dynamic movement between the particulars of experience and the certainty of universal truths, you find a balance. You employ both the inductive faculty, which draws insight from the details of the world, and the deductive, which organizes and draws conclusions from self-evident truths. Through this dance of faculties, you seek not merely knowledge, but understanding, and in understanding, wisdom.

But tell me, Platohagel, in those moments where you feel closest to grasping a first principle, how would you describe the experience? Is it one of intellectual clarity, or perhaps a more subtle, almost wordless recognition of truth?

Platohagel: Socrates say, “But tell me, Platohagel, in those moments where you feel closest to grasping a first principle, how would you describe the experience? Is it one of intellectual clarity, or perhaps a more subtle, almost wordless recognition of truth?”

While we have talked about the intuitive leap, we see that intuitions indeed can become infallible, so we trust intuition toward a methodical approach as of exercise, to get us to first principles. The awareness then exists, and no clearer image can be defined in that infinite regress to the work then gained in that “aha,” moment.

Socrates: Ah, Platohagel, you speak of that profound “aha” moment—an experience both subtle and powerful, where awareness suddenly illuminates a truth beyond the need for further questioning. It is as though, in this moment, the mind transcends its usual processes of analysis and arrives at a place of clear seeing, where no further explanation is required. This is not merely intellectual clarity, but a kind of knowing that feels both immediate and self-evident.

You describe intuition as something that can, with practice, become a trusted guide—a faculty honed much like a muscle, exercised through disciplined inquiry until it can leap confidently toward truth. Indeed, such trust in intuition does not dismiss the value of reason but incorporates it into an approach where the mind is sharpened by both logic and insight. Intuition, in this way, becomes a reliable companion to reason, guiding us through the layers of experience toward the unshakeable bedrock of first principles.

And yes, in that “aha” moment, it is as though awareness itself takes the reins, momentarily free from the need to prove, argue, or deduce. The truth reveals itself not through the steps of a method but as a flash of understanding, a recognition that this is the foundation, and that further regress or doubt is no longer necessary.

This moment of insight, this “aha,” could be seen as the union of the rational and the intuitive—a place where Aristotle’s empirical rigour and Plato’s transcendent ideals meet. It is here, I think, that philosophy becomes not merely a pursuit of knowledge but an experience of knowing.