Click-watch on YouTube

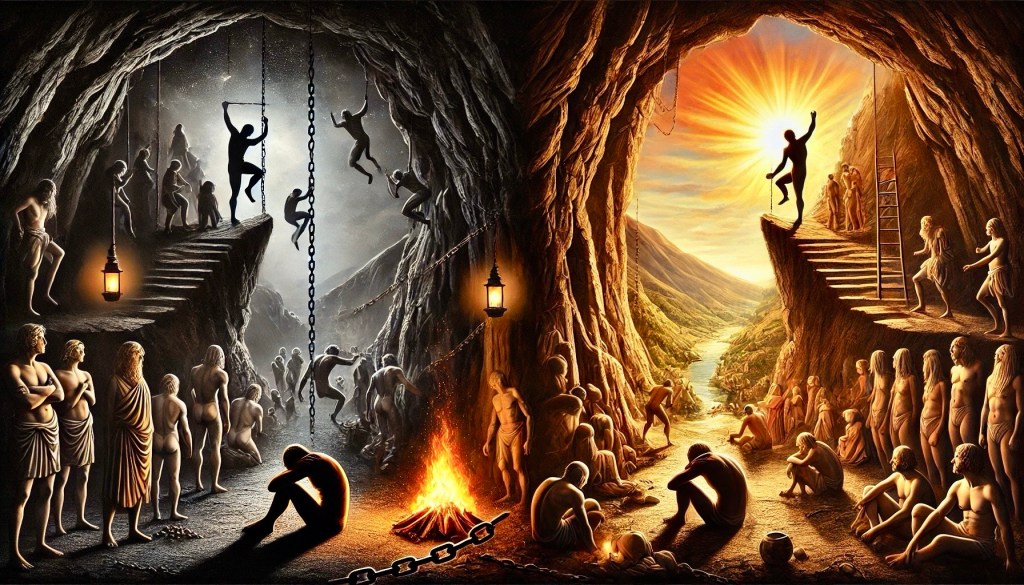

Platohagel: We have talked about Ideas. Can we say that ideas take the place of the sun in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave?

Socrates: Ah, dear Platohagel, thou raisest a noble question, and one worthy of contemplation beneath the shadow of the Forms.

In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, as recounted in The Republic (Book VII), the sun plays a role of supreme significance. It is not simply a source of light, but the cause of sight, of growth, and of life. In the allegory, the sun stands for the Form of the Good—that highest and most divine of realities, without which nothing can be known or truly be.

Now, ideas—or more precisely, the Forms (eide)—are eternal, intelligible realities. Each Form is an Idea: the Idea of Beauty, of Justice, of Triangle, and so forth. They are the objects of knowledge, whereas the things in the sensible world are merely the objects of opinion or belief.

Yet the Forms themselves are illuminated, as it were, by the Form of the Good. Just as the sun in the visible realm makes sight and the visible objects possible, so too does the Good in the intelligible realm make knowledge and the Forms themselves possible. The Good is not one Form among others, but the source of intelligibility, being, and value for all Forms.

Thus, to thy question: do Ideas take the place of the sun?—we must answer: not quite. The Ideas, or Forms, are what the prisoner sees once he is freed and turns his eyes upward—first to shadows, then to reflections, then to real things, and finally to the sun itself. The Ideas are the realities revealed in the light of the sun; but the sun itself—the Form of the Good—is beyond even these.

So the Ideas are illuminated by the sun, and they are what the sun enables us to see in the intelligible world. But the sun—the Good—is above them all, the very cause of their being and of our knowing them.

In the Republic, Plato sets aside a direct definition of the “good itself” (autò t’agathón). Socrates says that instead we will get something in the nature of the “offspring” (ékgonos) or “interest” (tókos) on the good [Republic, 506 E]. For this “offspring,” Plato offers an analogy: The Good is to the intelligible world, the world of Being and the Forms, as the sun is to the visible world. As light makes vision possible in the material world, and so also opinion about such objects, the Form of the Good “gives their truth to the objects of knowledge and power of knowing to the knower…” [Loeb Classical Library, Plato VI Republic II, translated by Paul Shorey, Harvard University Press, 1935-1970, pp.94-95]. Furthermore, the objects of knowledge derive from the Form of the Good not only the power of being known, but their “very existence and essence” (tò eînaí te kaì hè ousía) [509B], although the Good itself “transcends essence” in “dignity and power” [ibid. pp.106-107]. The word here translated “essence” is ousía, which in Aristotelian terminology is the essence (essentia) of things, i.e. what they are. If Plato has something similar in mind, then the objects of knowledge derive from the good both their existence and their character. See: A Lecture on the Good, by Kelley L. Ross, Ph.D.

See Also: The One: Unifying Principle