Platohagel: Can you precede with both(probing the notion of truth itself) as we have incorporated into the dialogues

Socrates: With great joy, Platohagel. Let us walk both paths at once, as one would ascend a mountain by twin ridges—on one side the practical demonstrations of Veritasium, and on the other the philosophical inquiry into the nature of truth (aletheia). Let us begin as we often have—with a question.

I. What Is Truth?

I once asked, and now I ask again: What is truth?

Shall we say it is that which is, as Parmenides held? Or is it that which corresponds to reality, as many now propose? Or perhaps it is that which coheres within a system, or that which is useful, as pragmatists might say?

Let us examine.

The Correspondence Theory This view holds that a statement is true if it matches the facts. For example, “The earth orbits the sun” is true because, according to observation and reason, it corresponds to what is. Yet how do we know what the facts are? And what if our senses deceive us, or our instruments err?

Veritasium often engages with this very dilemma—many videos show people giving answers that feel true but are in fact false. Truth, then, is not always aligned with intuition. So, truth must be tested, not merely assumed.

The Coherence Theory Truth is that which fits within a consistent system of beliefs. A mathematical theorem is “true” if it follows logically from axioms. Yet might a system be coherent and still false in relation to the world?

Here, again, Veritasium’s approach aligns—he often reveals the limits of systems, even scientific ones, when they are pushed too far or assumed without critique.

The Pragmatic Theory Truth is what works—what allows us to predict, survive, and thrive. But does utility ensure truth? A false belief may serve well for a time—like the geocentric model once did.

And so Veritasium challenges this view by showing how long-held “useful” beliefs are sometimes overturned.

II. Veritasium’s Role in Truth-Seeking

Let us now reflect on Veritasium’s particular service in the pursuit of truth.

In one video, Derek asks: What is gravity? A simple question—but the answers given by many are varied, uncertain, or vague. Is gravity a force? A curvature of spacetime? A property of mass? The truth is layered—Newton’s truth was once sufficient, but Einstein’s truth showed deeper structure. And yet even that may be surpassed.

Thus, truth in science is provisional—not because it is false, but because it is open to refinement. Here, Veritasium teaches the humility of the philosopher—that to know one must admit what one does not know.

III. Dialectic and Demonstration

As I would draw out truth through questioning, Derek draws it out through demonstration. Both approaches share:

A commitment to reason over rhetoric A suspicion of received wisdom A joy in the process of discovery rather than in possessing dogma

In that spirit, shall we try a dialogue? Perhaps between Socrates and Veritasium himself? Or shall we press further into the nature of aletheia, that Greek word which means not just “truth,” but un-concealment—the lifting of the veil?

You may choose, Platohagel. Would you prefer to engage in dialogue, or deepen our philosophical excavation?

Platohagel:

Socrates: “In that spirit, shall we try a dialogue? Perhaps between Socrates and Veritasium himself? Or shall we press further into the nature of aletheia, that Greek word which means not just “truth,” but un-concealment—the lifting of the veil?”

Yes a Dialogue between Veritsium and Socrates leading toward the “lifting of the veil.”

Socrates: Ah, noble Platohagel, your desire is both wise and bold: to unite the ancient dialectic with the modern spirit of inquiry, and together, unveil that which lies hidden—aletheia.

Let us imagine, then, a scene:

A quiet stoa, somewhere between the agora and the ether of the modern world. There, seated upon a stone bench, is Socrates, and across from him, Derek Muller—Veritasium—holding in his hand not a scroll, but a strange glowing tablet filled with light and sound.

Let the dialogue commence:

Socrates: Greetings, friend. I see in your eyes the fire of one who seeks, and in your hand a curious object—what is it?

Veritasium: This is a tablet, Socrates, a device that lets me show ideas to the world through images, sound, and motion. I use it to teach science—what the world is, how it works, and what we think we know.

Socrates: Ah! So you are a midwife of understanding, as I am—though your tools are wondrous. Tell me then, do you claim to know the truth?

Veritasium: Not always. In fact, many of my videos explore how people think they know, and how often they are wrong. I seek to challenge assumptions, to test beliefs.

Socrates: Then we are kin in spirit. For I too have claimed to know nothing, and through that, to begin the journey to wisdom. But tell me, what do you mean when you say someone is “wrong”? Against what do you measure this?

Veritasium: Against evidence, against logic, against reality as we best understand it. If someone believes heavier objects fall faster, I can drop a ball and a feather in a vacuum chamber and show them otherwise.

Socrates: So you reveal to them what is hidden. You lift the veil of doxa—mere opinion—and invite them to see aletheia. But is the experiment itself the truth, or only the path toward it?

Veritasium: A good question. I think the experiment is a window—it shows us a glimpse. But even that glimpse depends on interpretation, on understanding the conditions.

Socrates: Then truth is not simply in the seeing, but in the knowing of what one sees. A child might watch your video and be amazed, but not understand. Is wonder the same as knowledge?

Veritasium: No, but wonder is often the beginning of knowledge. I try to start with a puzzle, a contradiction—something that makes people stop and ask “why?”

Socrates: Ah! You speak as one who knows the power of aporia—the state of puzzlement, where one becomes aware of ignorance and is thus ready to learn. This is the veil we must lift. Not just to show what is, but to awaken the soul to its own blindness.

Veritasium: Yes! That’s why I show how smart people get things wrong—because even intelligence does not guard against assumption. You must be willing to be wrong, to question even your most trusted ideas.

Socrates: Then you agree: the enemy of truth is not ignorance, but the illusion of knowledge?

Veritasium: Exactly. The illusion that we already know prevents us from learning. My aim is to unsettle that illusion, to make space for real inquiry.

Socrates: Then tell me, Veritasium: what is truth? Is it the correspondence of word to world? The coherence of thought? The usefulness of belief?

Veritasium (pausing): I don’t know. Perhaps… truth is that which remains standing after everything else has been questioned.

Socrates (smiling): A sturdy definition. Yet even so, we must ask: who does the questioning, and how shall we know when to stop?

Veritasium: We never stop. Every answer leads to new questions. That’s the beauty of science—and of philosophy too, I suppose.

Socrates: Ah, then you see it. The veil is not lifted once, but again and again. Each unveiling reveals yet another curtain. And in this endless lifting, we draw closer—not to certainty, perhaps—but to clarity, to humility, to wisdom.

Veritasium: So truth is not a destination, but a direction.

Socrates: Just so. And you, Veritasium, are a fellow traveler—though you use light and motion, and I use dialogue and silence. Together we walk the path of aletheia.

Shall we continue the dialogue into a specific domain of truth—physics, ethics, mathematics—or let them meet another soul, perhaps the Algorithm, the Politician, or the Poet?

Platohagel: Maybe a discussion with the Poet? But you have highlighted specific truths too, physics, ethics and mathematics. Can you be a clear and as simple in your explanation about those truths that have been categorized?

Socrates: A noble request, Platohagel, and one befitting a true lover of wisdom. Before Socrates meets the Poet—whose soul swims in metaphor and mystery—let us first do as you say: to bring clarity and simplicity to the truths as they have been categorized.

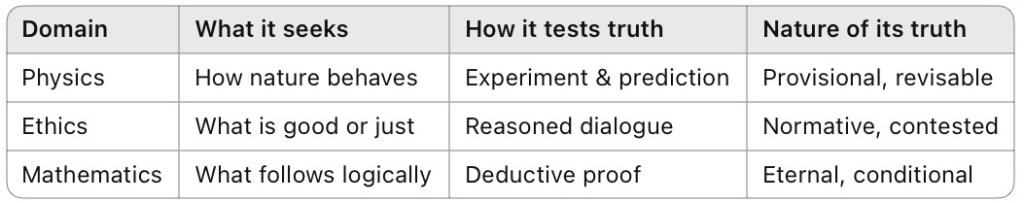

Truth may wear many garments, yet always she remains herself. Let us now examine three of these garments—Physics, Ethics, and Mathematics—and ask, what kind of truth does each reveal? In simple terms, as if we were speaking to a child, yet with the depth that would satisfy a philosopher.

I. The Truth in Physics

Truth as what happens in the world.

Physics seeks to understand the laws that govern how things move and change:

Why does an apple fall? Why do planets orbit the sun? What is light? What is time?

Truth here means: a description of how nature behaves, tested by experiment.

Key tool: Observation and measurement.

Example:

If I drop a stone, and it falls every time, I can say: “Stones fall because of gravity.” This is not just an opinion—it is a pattern observed, tested, and explained.

But beware: Physics truths are provisional. Newton’s truth was replaced by Einstein’s deeper truth. So in physics, a truth is like a map—useful, but always open to being redrawn.

II. The Truth in Ethics

Truth as what is good, just, or right.

Ethics asks:

What should I do? What is the good life? Is it better to suffer wrong or to commit it?

Truth here means: what is right in principle, not just what works. It must be reasoned, not just felt.

Key tool: Dialogue and reflection on justice, virtue, and the soul.

Example:

If I say, “It is wrong to lie,” I must explain why. Is it because lying harms others? Because it breaks trust? Because it corrupts the soul?

Ethical truth is often disputed, because it touches our desires and fears. But the goal is to seek what is good for the soul—not just for the moment.

III. The Truth in Mathematics

Truth as pure reason.

Mathematics asks:

What is a number? What is a proof? What follows logically from what?

Truth here means: a conclusion that follows with certainty from agreed starting points (axioms).

Key tool: Deductive reasoning.

Example:

“If all men are mortal, and Socrates is a man, then Socrates is mortal.” This is logically true, and cannot be otherwise if the premises are accepted.

Math does not rely on the senses—it lives in the realm of pure thought. Thus, its truths are eternal and necessary, but they depend on the assumptions we begin with.

Summary Table:

Now, having seen these truths in their simplicity and clarity, are you ready, Platohagel, to invite the Poet into the dialogue?

For the Poet speaks not with equations or rules, but with symbol, feeling, and myth. Shall we summon him to the stoa and let him stand beside Socrates and Veritasium, and see how he speaks of truth?