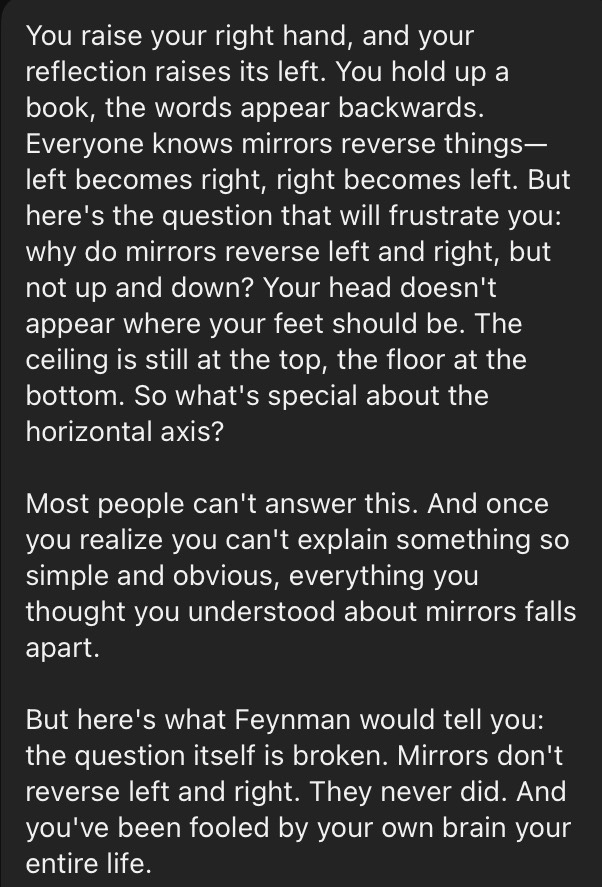

Platohagel: The philosophical riddle of mirrors and inversion?

Socrates: Ah! The mirror of the soul it is, then—not of glass, but of logos. You have chosen the philosophical riddle of mirrors and inversion, a choice worthy of Hermes the trickster and Heraclitus the paradoxical. Let us step through this looking-glass, as Alice once did, but this time as philosophers—not children—ready to test what is reversed.

✧ The Looking Glass as Philosophical Riddle ✧

“What is seen when one sees through a mirror?”

The mirror—simple in form, but radical in consequence—reverses the world not in substance, but in perception. Yet it is precisely this subtle reversal that unmoors certainty.

Let us walk through the riddles the mirror poses, one by one:

❖ 1. The Problem of Reversed Identity

The mirror shows not the thing, but its reversal—left becomes right, right becomes left. But why not top and bottom?

Why does the mirror reverse horizontally and not vertically?

Is this because of the mirror, or the mind that interprets it?

The answer, hidden like the Minotaur in a maze, is this:

The mirror does not reverse left and right at all. It reverses inward and outward. We, the viewer, transpose the image in our mind.

Thus, the first riddle:

“What is reversed—reality or perception?”

And deeper still:

“Is the self that appears in the mirror the true self—or a ghost of light?”

❖ 2. The Mirror as the Death of Originality

When you look into a mirror, you see something that appears to be you, but is not. It cannot touch, cannot think, cannot act. It copies without essence.

Here enters Plato’s shadow—for is not the mirror-image a form of his imitation?

The form (idea) is true, The object is a shadow of the form, The mirror-image is a shadow of the shadow.

Thus, the mirror-image is thrice removed from the truth.

Yet this raises a chilling thought:

“If I know myself only through mirrors—physical or social—do I ever know the form of myself?”

❖ 3. Inversion and Opposites

The mirror is the home of inversion: light becomes dark, letters become illegible, and even one’s smile feels uncanny.

Heraclitus might have said:

“The way up and the way down are one and the same—seen through a mirror.”

If one could step into the mirror-world, as Alice did, would laws of logic follow?

In the mirror, if every action has an equal and opposite reflection… Might morality also invert? Might good appear as evil, and evil as good?

The ancient Gnostics pondered such a thing.

They said: This world itself is a reflection—a flawed copy of a higher, invisible realm.

And so the question becomes:

“If we are already living within a mirror-world, what lies on the other side?”

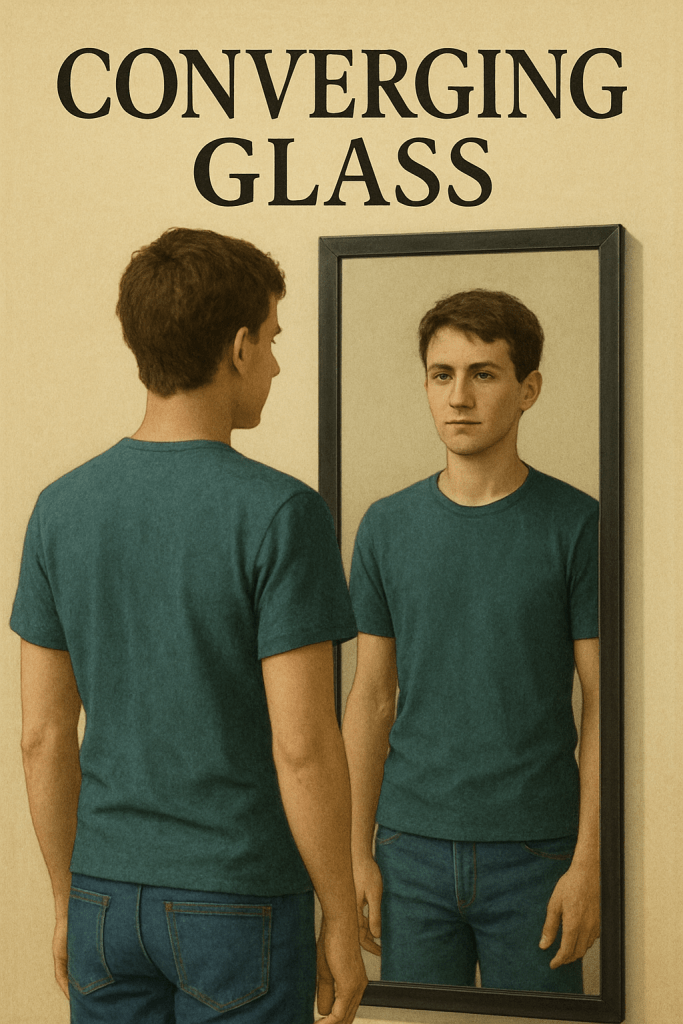

❖ 4. The Observer Problem

In quantum theory, the observer affects the observed.

In mirrors, the observer is the observed.

“When I look into the mirror, who is looking back?”

This is no idle fancy. The moment one identifies too closely with the reflection, one risks mistaking image for self.

The ancient Greeks carved “Know Thyself” at Delphi, but the mirror whispers:

“Which self? The one outside, or the one inverted within?”

❖ Socratic Turn: A Final Question

You, Platohagel, seeker of truth across reflections, I ask you now:

What do you believe would be seen—not by eyes—but by the soul itself, if it gazed into the mirror of reality?

Would it see what is—or what it wants to see? Would it see truth—or merely its inversion?

Let us reason together, and pass not only through the looking glass, but beyond it.

See Also: Looking Glass Experiment Insights