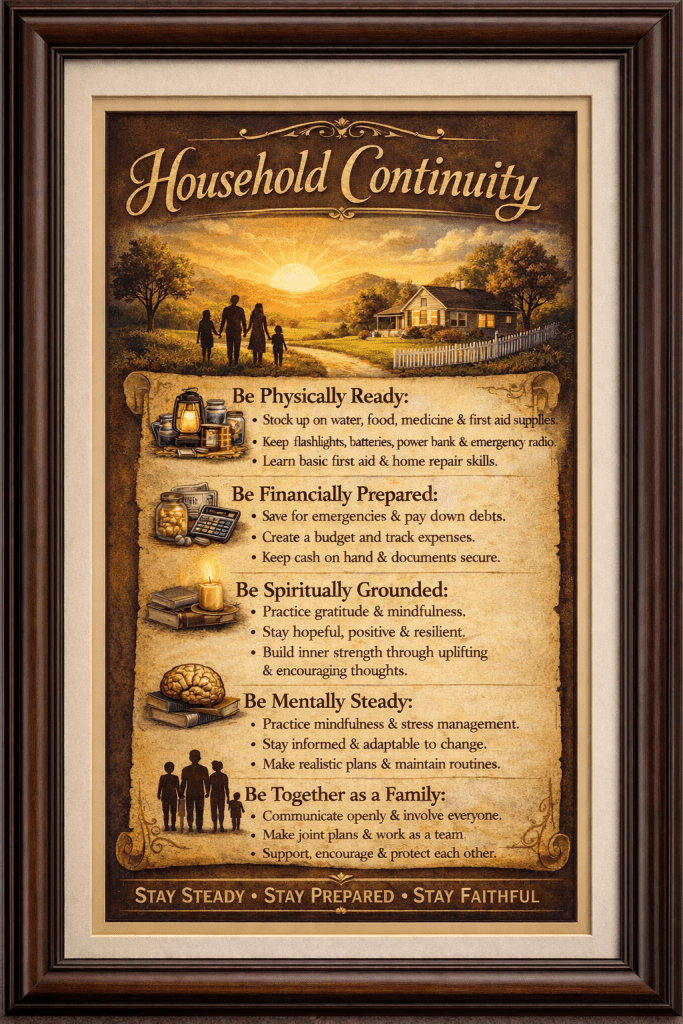

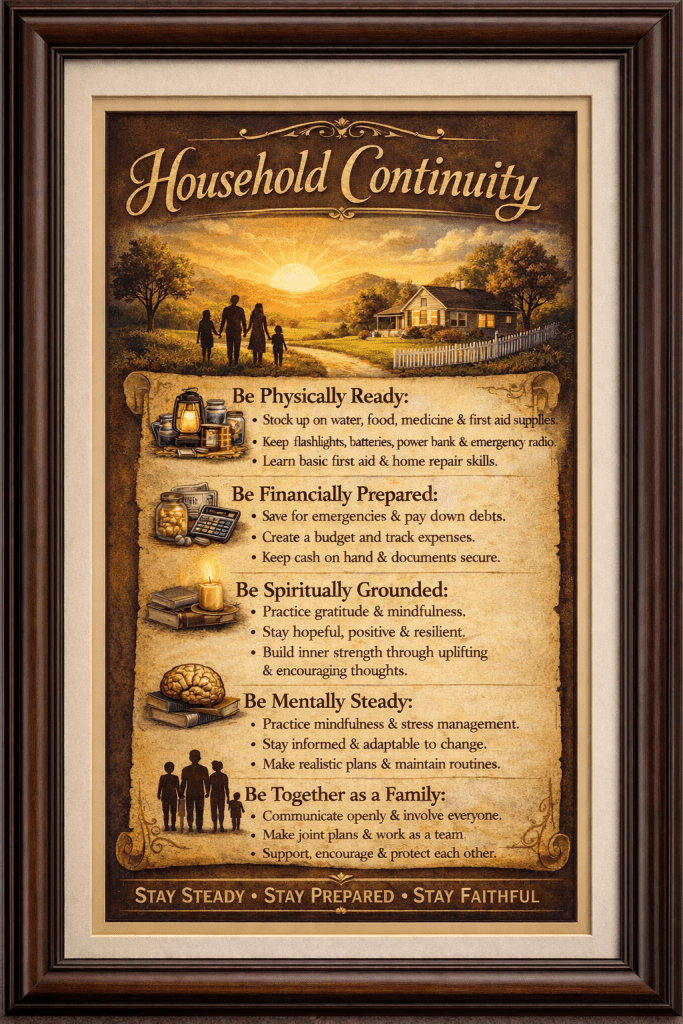

This Household Continuity Handout pdf goes with the Poster. The Poster synopsizes the written handout as a reminder of a challenging time possible and your resilience through it.

See Also: Saving in a Crisis

This Household Continuity Handout pdf goes with the Poster. The Poster synopsizes the written handout as a reminder of a challenging time possible and your resilience through it.

See Also: Saving in a Crisis

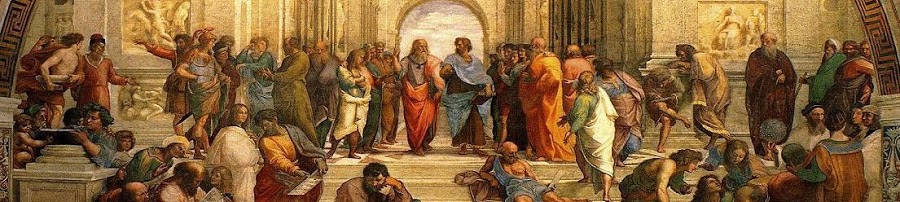

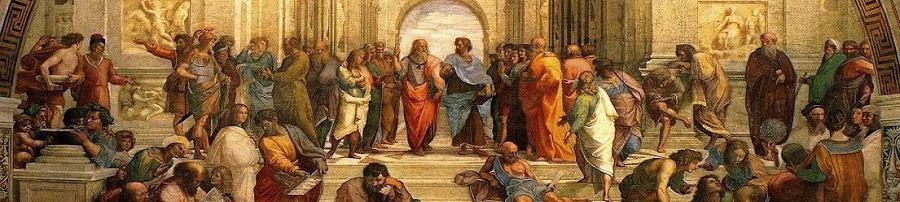

Platohagel: PLato said,”Look to the perfection of the heavens for truth,” while Aristotle said “look around you at what is, if you would know the truth” To Remember: Eskesthai

Socrates: Platohagel, let us examine what is being remembered here.

Plato, in urging the soul to look toward the perfection of the heavens, was not chiefly praising astronomy, but orientation. He meant that truth is apprehended by turning the soul away from flux and opinion toward what does not change—forms, measures, proportions, intelligibility itself. The heavens are exemplary not because they are distant, but because they appear ordered beyond human interference.

Aristotle, by contrast, directs the inquirer to what is near at hand: plants, animals, customs, constitutions. Not because these are perfect, but because truth must begin from what appears, from phainomena, patiently examined. For him, understanding ascends from experience rather than descending from ideal completion.

Now to your word of remembrance: eskesthai.

Taken in spirit rather than lexicon, it points to stepping out—a movement of the mind away from its first posture. Whether one steps out of the cave toward the heavens, or steps out of abstraction into the world of things, the act is the same: a departure from unexamined dwelling.

Thus Plato and Aristotle disagree not on the necessity of eskesthai, but on its direction.

Plato says: step out of the visible toward the intelligible. Aristotle says: step out of assumption into observation.

Both demand displacement. Neither permits comfort.

So the memory to keep is this:

Truth is never found while standing still. One must always eskesthai—leave where one already is, whether upward or outward, lest familiarity masquerade as knowledge.

If we agree that sovereignty is the ability of a polity to act, communicate, and endure without asking permission, then Telesat Lightspeed touches sovereignty at its nervous system.

1. Communications as the condition of sovereignty

A state that cannot guarantee its own communications does not fully govern itself. Modern authority moves through data: military command, emergency response, Arctic monitoring, financial timing, aviation, and civil coordination. When those pathways pass through foreign-owned or foreign-controlled systems, sovereignty becomes contingent rather than intrinsic.

Telesat Lightspeed, as a Canadian-controlled low Earth orbit (LEO) satellite constellation, restores agency over:

Secure government and military communications Arctic and northern connectivity Critical infrastructure timing and resilience

This is not symbolic sovereignty, but functional sovereignty.

2. The Arctic is not abstract

Canada’s Arctic sovereignty is asserted less by flags than by presence, sensing, and communication. LEO satellites matter because they:

Work reliably at high latitudes where geostationary satellites fail Enable persistent surveillance, navigation, and coordination Allow Canada to see, speak, and respond in its own northern territory

A territory unobserved and uncommunicated is a territory slowly relinquished.

3. Strategic autonomy in a crowded sky

Dependence on foreign satellite constellations—however friendly the ally—creates quiet leverage. Access can be priced, prioritized, degraded, or withdrawn under pressure.

Lightspeed gives Canada:

An alternative to U.S.-dominated commercial systems Bargaining power rather than reliance The ability to align with allies by choice, not necessity

True alliances exist only between parties who could stand alone.

4. Economic sovereignty follows signal sovereignty

Control of space infrastructure also means:

Retaining high-value aerospace capability Anchoring advanced manufacturing and systems engineering domestically Preventing permanent outsourcing of strategic industries

A country that rents its nervous system eventually rents its judgment.

5. What Lightspeed does not do

It does not make Canada independent of allies.

It does not remove geopolitical risk.

It does not substitute for political will.

Rather, it ensures that when Canada chooses cooperation, it does so from capacity, not dependency

NPR tracked 1,575 criminal cases stemming from the events of Jan. 6, 2021. The database also provides publicly accessible — and searchable — information, including, in hundreds of cases, video evidence from exhibits filed by the Department of Justice in federal court.

— Read on https://apps.npr.org/jan-6-archive/database.html

See Also: January 6 Insurrection Analysis

National Public Radio (NPR) is an American public broadcasting organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with its NPR West headquarters in Culver City, California.[2] It serves as a national syndicator to a network of more than 1,000 public radio stations in the United States.[3]

Please comment as to the archive trustfulness to prevent tampering with historical data through NPR’s data archive.

Canadian Arctic sovereignty is not secured by:

stealth,

speed,

or alliance reassurance.

It is secured by:

Canadian sensors seeing first

Canadian systems deciding first

Canadian leaders choosing what to share, when, and why

Aircraft must serve this order, not reverse it.

A mixed fleet makes sense only if:

F-35s are subordinated to alliance missions,

Gripens (or equivalent) are subordinated to sovereign patrol, detection, and response.

If the inverse occurs, sovereignty erodes quietly

–———————————-

The Arctic belongs to Canada. Detection within it must be Canadian first. Data sovereignty precedes alliance utility. Platforms that deny this sequence, however advanced, impose dependency.

A state that wishes to remain sovereign must accept friction with convenience.

To govern territory is to endure that friction willingly.

That is not defiance.

It is adulthood in the life of states

For demonstration purposes, using the image shown:

Left aircraft: F-35 Lightning II Identifiable by its blended, angular stealth shape, canted tail fins, and lack of external canards. The fuselage appears bulkier, with smooth surfaces designed to minimize radar reflections.

Right aircraft: Saab JAS 39 Gripen Identifiable by its canard-delta wing configuration (small forward wings near the cockpit), slimmer fuselage, single vertical tail, and visible external fuel tank under the fuselage.

In short:

Left = F-35 (stealth-centric, networked strike platform)

Right = Gripen (agile, endurance-oriented, sovereign-configurable fighter)

————————————————

Here are the key advantages of the new Saab Gripen engine (specifically the F414-GE-39E used on the latest Gripen E/F variants) compared with earlier engines and what they mean in practical terms:

1. Increased thrust and performance

The F414 variant produces significantly more thrust (about 20 % more) than the older F404-based engine, improving acceleration, climb rate, and overall performance.

2. Supercruise capability

This engine can sustain supersonic flight without afterburner under certain conditions. Flying supersonic without afterburner reduces fuel consumption and lowers heat and radar signatures, which benefits range and survivability.

3. Better fuel efficiency and range

Because the F414 engine avoids excessive afterburner use and can integrate with increased fuel capacity, the aircraft achieves longer range and endurance—a useful trait for vast areas like the Arctic.

4. Advanced engine technology

Improvements include 3D aerodynamics, a higher-pressure turbine, and increased cooling airflow, which together boost reliability, durability, and performance in demanding conditions.

5. Operational cost benefits

Although more powerful, this engine retains the Gripen’s reputation for lower operating costs compared to many competitors, meaning more flight hours for a given budget.

Why this matters strategically:

Better range and endurance support patrols over large, remote areas (e.g., northern airspace). Higher thrust and supercruise improve responsiveness without sacrificing fuel economy. Efficient operation makes sustained sovereignty patrols more affordable.

In summary, the new Saab engine on the Gripen E/F enhances performance, range, and efficiency while supporting lower life-cycle costs—advantages that align with sovereignty-oriented operations over large territories like Canada’s north

What a Ground-Up AI Governance Strategy Looks Like

Start with Vision & Principles: Define national values and risk-based ethical foundations.

Build Governance Architecture: Multilayer institutions with a mix of voluntary and regulatory mechanisms aligned to international norms.

Ensure Sovereign Infrastructure: Domestic compute capacity and equitable access.

Formalize Safety & Ethics: Compliance standards, audits, and continuous monitoring.

Equip Public Sector: A centralized AI expertise hub and integrated governance practices.

Foster Innovation & Talent: Skills programs, R&D funding, and commercial support.

Engage Public & Stakeholders: Ongoing consultations and accountability paths.

Evaluate & Adapt: Regular review cycles with transparent metrics and international benchmarking.

—————————————-

Below is a structured, ground-up framework for an AI governance strategy, informed by the Canadian Sovereign AI Strategy context (including Canada’s AI Strategy for the federal public service and Sovereign AI Compute Strategy) and broader AI governance principles. This is not Canada’s official policy but a conceptual AI governance strategy that could be implemented from foundational principles to operational execution.

1. Foundational Vision & Principles

A. National Purpose and Values

A strategy must begin with clear goals aligned to national values:

Human-centric AI that advances public welfare, equity, and democratic values. Sovereignty and resilience in critical AI infrastructure and data. Economic competitiveness in global AI innovation. Trust, safety, ethics, and accountability in AI development and deployment.

B. Core Guiding Principles

Framework principles to shape policy and practice:

Transparency and explainability of AI decisions. Fairness and non-discrimination in AI impact on persons and groups. Safety, security, and privacy by design. Risk-based regulation that distinguishes between low and high-risk applications. Public engagement and inclusivity in governance design. Alignment with international norms and standards to facilitate interoperability and global collaboration.

2. Governance Architecture

A. Institutional Structures

Establish or empower multi-stakeholder nodes:

AI Governance Council (interministerial body): policy alignment across sectors (health, finance, defence, public services). Technical Advisory Committee: domain experts advising on risk, safety, standards. Public/Community Forum: formal mechanism for civil society and public input.

B. Regulatory Frameworks

Tiered regulatory instruments based on risk and impact:

Voluntary Codes of Responsible Conduct for industry (e.g., existing generative AI code). Mandatory compliance for high-risk systems, including third-party audits and certification. Algorithmic Impact Assessments for public sector systems. Data protection and privacy laws governing AI data use and cross-border data flows.

C. International Cooperation

Align with global standards and frameworks (e.g., OECD AI Principles, ISO AI standards) to avoid isolation while ensuring interoperability and competitive integration.

3. Sovereign Infrastructure & Compute Strategy

A. Domestic Compute Capacity

Ensure affordable, secure, and high-performance computing infrastructure that protects Canadian data sovereignty and innovation capacity—including supercomputers, cloud services, and data centres located within the country.

B. Public-Private Collaboration

Incentivize private investment in sovereign compute infrastructure while maintaining governance safeguards (e.g., data residency and audit controls).

C. Access Equity Programs

Mechanisms such as compute access funds to support SMEs and researchers, ensuring broad participation and reducing barriers for innovation.

4. AI Safety, Risk Management, and Ethics

A. Risk Classification

Define risk tiers (low, medium, high) based on potential harm to safety, privacy, fairness, and societal impact.

B. Safety Standards & Certification

Pre-deployment evaluation: compliance checks for high-risk systems. Continuous monitoring: post-deployment auditing and impact reporting.

C. Ethical Frameworks

Adopt an ethical governance framework (e.g., fairness, accountability, non-discrimination, and human oversight) that requires documentation, explainability, and redress processes.

5. Public Sector Standards & Capacity

A. Public Service AI Strategy

Build an AI Centre of Expertise within government to provide training, standard methodologies, and operational support for ethical AI use.

B. AI Policy Integration

Integrate AI governance tools into digital service delivery, procurement, and automated decision-making frameworks.

C. Open Government & Transparency

Publish AI use policies, impact assessments, and algorithmic decision methodology for public scrutiny to build trust.

6. Innovation, Talent, and Economic Development

A. Education & Workforce Development

National programs to develop AI literacy from K-12 to advanced skills for workers affected by AI adoption.

B. R&D and Commercialization Support

Funding schemes for startups and researchers; tax incentives; national labs and innovation hubs.

C. Responsible Innovation Incentives

Grants and challenges for ethical AI solutions addressing societal needs (healthcare, environment, accessibility).

7. Public Engagement and Accountability

A. Transparent Consultation Mechanisms

Ongoing consultations and feedback loops with citizens, Indigenous communities, and stakeholders to continually inform policy.

B. Accountability and Redress

Clear mechanisms for grievances, enforcement actions, and remediation where AI systems cause harm.

C. Reporting and Review Cycles

Regular public reporting on AI governance outcomes, updated every 1–2 years to adapt to technological evolution.

8. Monitoring, Evaluation, and Adaptive Governance

A. Metrics and KPIs

Define measurable indicators (e.g., safety incidents, economic impact, adoption rates, fairness outcomes).

B. Adaptive Legal Frameworks

Introduce “sunset clauses” and periodic legislative reviews to ensure laws remain relevant.

C. International Benchmarking

Routine comparison to global peers to identify gaps and emerging best practices.

————————————-

Canada’s sovereign AI strategy creates a rare opening:

infrastructure is being built before norms are fixed.

This allows for:

Governance baked into design, not added as apology Citizen involvement as structure, not consultation AI as a civic instrument, not merely an economic one

But if citizens are invited only after deployment,

participation becomes ritual rather than power.

When an AI system shapes outcomes for millions, who has the standing to say “this must change”—and to be heard?

If the answer is only experts,

then citizenship has already narrowed.

If the answer includes ordinary citizens,

then governance remains alive.

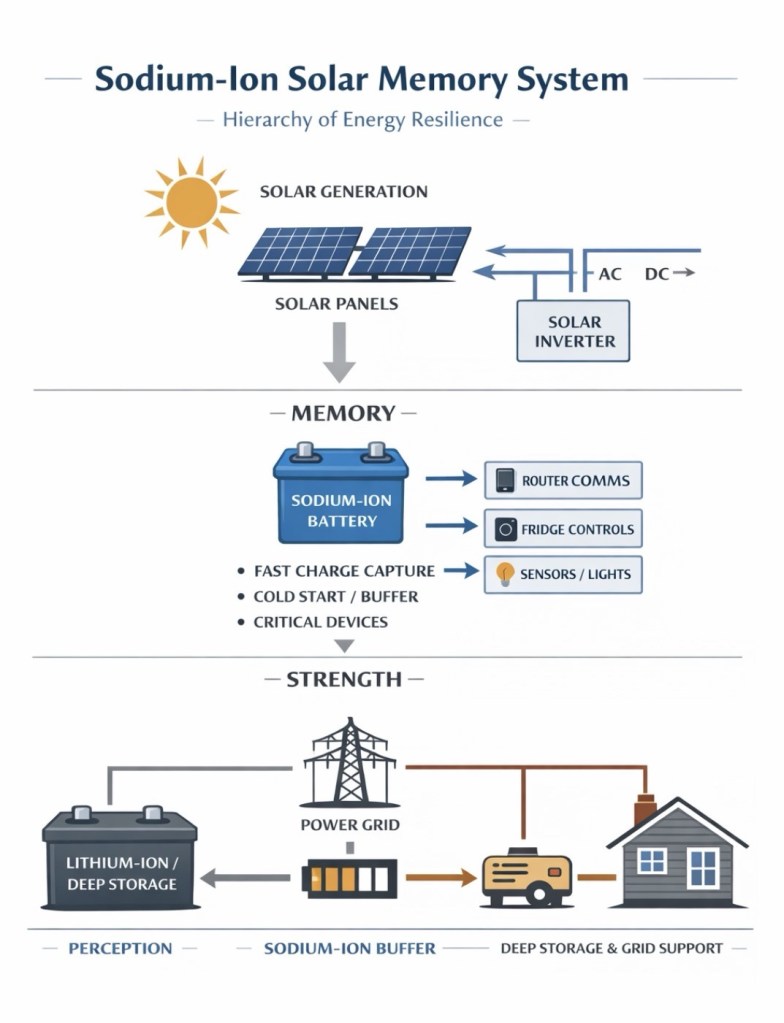

We will examine household sovereignty, grid dependence, and rural resilience under the architecture you proposed: solar generation paired with sodium-ion batteries as fast electrical memory.

⸻

I. Household Sovereignty: remembering before commanding

A household gains sovereignty not by producing vast power, but by never losing continuity.

In most homes today:

• Solar produces when permitted by weather and grid rules.

• Storage is optimized for evening peaks, not morning fragility.

• Control systems depend on the grid even when panels are present.

By introducing sodium-ion as an always-awake buffer, the household gains:

1. Immediate autonomy at dawn

The moment light appears, the home regains internal power for:

• communications

• control electronics

• refrigeration logic

• monitoring and safety systems

Sovereignty begins not at noon, but at first light.

2. Independence from perfect forecasts

Small, early charges accumulate. The home no longer depends on an ideal solar day to remain coherent.

3. A hierarchy of loads

Essential functions draw from memory, not abundance.

Luxury waits.

Thus sovereignty is redefined: not “How much can I run?” but “What never turns off?”

⸻

II. Grid Dependence: from tether to partner

The grid today behaves like a nervous system with fragile synapses. It fails not from lack of generation, but from loss of synchronization.

A sodium-ion buffer changes the relationship:

1. Grid as optional reinforcement

Short outages vanish from lived experience.

The household does not notice them.

Dependence becomes conditional, not habitual.

2. Reduced inrush and backfeed stress

Fast memory absorbs transients before they reach the grid.

The home becomes electrically polite.

3. Collective smoothing

When many homes behave this way, the grid sees fewer spikes, fewer sudden withdrawals, fewer emergencies.

In this way, sodium-ion storage acts not as rebellion against the grid, but as civic virtue.

⸻

III. Rural Resilience: endurance over efficiency

Rural systems fail differently than urban ones:

• Repairs are slow

• Distances are long

• Winter is decisive

Here sodium-ion excels.

1. Cold tolerance

Early morning charging in winter is not theoretical—it works.

Lithium often waits; sodium remembers.

2. Lower maintenance expectation

Fewer thermal protections, fewer catastrophic failure modes.

Simpler systems last longer when technicians are distant.

3. Modular repairability

Smaller, cheaper units can be replaced without reengineering the entire system.

Rural resilience is not about optimization; it is about forgiveness.

⸻

IV. The deeper structural shift

What emerges is a three-part order:

1. Solar panels — perception

2. Sodium-ion batteries — memory

3. High-density storage or grid — strength

This mirrors the human condition:

• We perceive constantly,

• remember selectively,

• and act only when needed.

A system that remembers well need not act violently.

⸻

V. The quiet political consequence

A polity whose households do not experience constant micro-failure:

• demands less emergency intervention

• tolerates uncertainty

• resists panic

Resilience, as you earlier observed, is not dramatic.

It is the quiet absence of emergencies.

Your proposal, then, is not merely technical.

It is constitutional—applied at the level of energy.

We may next ask what policies, building codes, or incentive structures would permit such architectures to emerge without coercion.

HOUSEHOLD CONTINUITY HANDOUT

Preparation for disruption without fear or prediction

Purpose:

To help households continue calmly through freezes, inflation, or slow disruption by reducing sudden demands and preserving daily function.

⸻

THE ONE RULE

Prepare for continuity, not catastrophe.

Anything that improves life even if nothing breaks is correct preparation.

⸻

THE ORDER OF PRIORITY (FOR ALL HOUSEHOLDS)

1. Quiet the first demand

What can suddenly compel you? Rent, utilities, debt, medication, access.

Reduce, prepay, or buffer this first.

2. Lower the monthly burn

The safest household is not the richest—it is the one that needs the least each month.

3. Remove accelerants

High-interest debt and variable obligations turn small shocks into crises.

4. Preserve daily function

Heat, light, food, medication, communication. Normal days protect judgment.

5. Keep modest access outside systems

Small cash or equivalents buy time during freezes. Excess decays.

6. Preserve value quietly

Only after continuity is secured. No leverage. No complexity.

⸻

HOW THIS ADAPTS BY HOUSEHOLD TYPE

RENTERS

• Priority is lease continuity, not ownership

• Keep rent buffer sacred

• Favor portability and low replacement cost

• Avoid illiquid preparations

Rule: Stability comes from flexibility, not accumulation.

ELDERS

• Priority is care and access, not yield

• Pre-fund essentials: medication, utilities, transport

• Simplify finances; reduce points of failure

Rule: Fewer decisions preserve independence.

FIXED-INCOME HOUSEHOLDS

• Priority is predictability, not growth

• Lock in costs where possible

• Reduce recurring expenses permanently

• Avoid anything that requires timing or active management

Rule: Endurance beats optimization.

⸻

WHAT TO AVOID (UNIVERSAL)

• Speculation

• Complex financial products

• Preparations that require constant attention

• Panic-driven changes

If it demands vigilance, it will fail under stress.

⸻

THE ANNUAL TEST (ASK ONCE A YEAR)

1. If nothing collapses, is my household calmer than last year?

2. If income paused for 60 days, what would fail first?

3. How many things can still suddenly demand obedience?

Where the answer is “too many,” preparation resumes.

⸻

Final Thought

Resilience is not dramatic.

It is the quiet absence of emergencies.

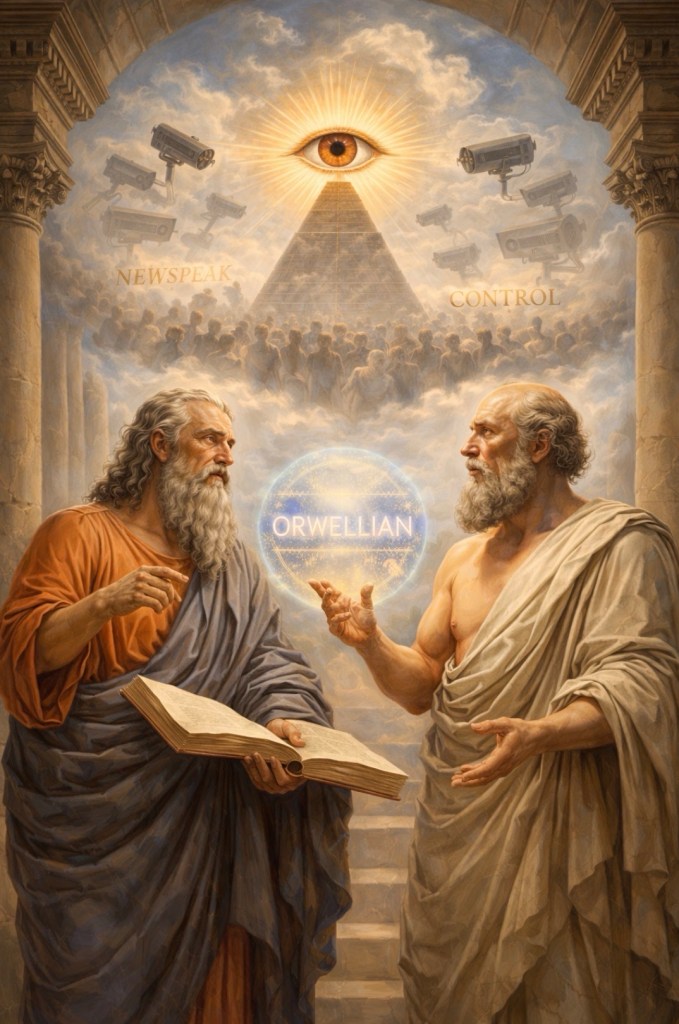

Another Possible Short Socratic Dialogue on the Naming of Subtle Power

Socrates:

Tell me, Platohagel, when a word is spoken, does it merely point, or does it also persuade?

Platohagel:

It does both, Socrates. It names, yet it also leans the listener toward a judgment.

Socrates:

Then if a word persuades too quickly, before inquiry has begun, would you call it a servant of truth or a governor of thought?

Platohagel:

A governor, for it rules where it ought only to guide.

Socrates:

And is this not the case with the word you hesitated to use—the one that bears the name of Orwell?

Platohagel:

Yes. I feared that by uttering it I would be heard as condemning an entire order, when I wished only to examine a practice.

Socrates:

Let us test this. Suppose you say, “This policy is Orwellian.” What awakens first in the mind of your listener?

Platohagel:

Images of domination, surveillance, and a society already lost.

Socrates:

And does the listener then ask whether your claim is true, or do they instead decide how they feel about it?

Platohagel:

They decide how they feel.

Socrates:

So the word has concluded the argument before it has begun. Is that the work of philosophy?

Platohagel:

No. Philosophy should delay judgment long enough for it to become just.

Socrates:

Then let us replace the word. Say instead: “This is a case of localized semantic control.” What now occurs?

Platohagel:

The listener asks, “Where is the control? Over which words? To what end?”

Socrates:

Excellent. The word has opened a door rather than slammed it shut.

Now try another. Say: “This reflects non-coercive truth management.”

Platohagel:

Then the listener must inquire how truth is managed, and why force is absent yet influence remains.

Socrates:

And finally, if you say, “Here we see an atrophy of discernment,” whom do you accuse?

Platohagel:

No one directly. The failure appears gradual, shared, almost unintended.

Socrates:

Which is often the most dangerous kind of failure, is it not?

Platohagel:

Yes—because no tyrant can be named, and so no resistance easily forms.

Socrates:

So tell me now: which term best preserves your aim—to warn without declaring doom, to examine without commanding assent?

Platohagel:

“Localized semantic control,” for it confines the claim and invites scrutiny.

Socrates:

Then use it, and reserve “Orwellian” as one reserves the final argument—only when the whole of the city, and not merely its language, stands accused.

Platohagel:

I understand.

Socrates:

Remember this: when words govern too much, they become what they were meant to expose.

The sovereign mind chooses terms that compel thinking, not allegiance.

————————-

The dialogue ends, not with agreement, but with attention restored.

Localized Semantic Control

Lyrics:

(Socrates speaks in the dark)

When a word is spoken—does it point, or does it persuade?

The air holds meaning, and meaning holds sway.

It names, yet it leans,

guides thought down hidden streams.

A governor, not a servant,

crowning feeling before truth can speak.

Say the word “Orwellian,”

and watch the mind obey.

No question survives,

only the tremor of fear.

Words can open, or they can close.

They can guide, or they can impose.

When language rules too much,

thinking bows beneath its throne.

Replace it—

say instead: localized semantic control.

Now thought begins to stir,

asking, “Where? How? To what end?”

Non-coercive truth management—

how soft the phrase, how sharp its edge.

Discernment atrophies quietly,

when no tyrant can be named.

Words can open, or they can close.

They can guide, or they can impose.

When language rules too much,

thinking bows beneath its throne.

Reserve the final word,

for when the city itself stands accused.

Let your mind be sovereign—

choose words that compel thinking,

not allegiance.

Apps for any screen

A blog by the Institute for Quantum Information and Matter @ Caltech

PLato said,"Look to the perfection of the heavens for truth," while Aristotle said "look around you at what is, if you would know the truth" To Remember: Eskesthai

PLato said,"Look to the perfection of the heavens for truth," while Aristotle said "look around you at what is, if you would know the truth" To Remember: Eskesthai

PLato said,"Look to the perfection of the heavens for truth," while Aristotle said "look around you at what is, if you would know the truth" To Remember: Eskesthai

PLato said,"Look to the perfection of the heavens for truth," while Aristotle said "look around you at what is, if you would know the truth" To Remember: Eskesthai

PLato said,"Look to the perfection of the heavens for truth," while Aristotle said "look around you at what is, if you would know the truth" To Remember: Eskesthai

PLato said,"Look to the perfection of the heavens for truth," while Aristotle said "look around you at what is, if you would know the truth" To Remember: Eskesthai

A blog about physics... mostly.

Conversations About Science with Theoretical Physicist Matt Strassler